How Digital Nervous Systems Can Raise Your Organizational IQ

As technology accelerates the flow of information, businesses have a new role model: computer networks.

August 09, 2017

These days, customer service is a two-way information pipeline that involves much more than phone calls. | iStock/PeopleImages

In the late 1990s, I developed, together with my Stanford research team, the concept of Organizational IQ, along with a way to measure it and a methodology for improving it. At the time, managers were already experiencing accelerating development cycles; intensifying global competition; and increasing demands from consumers, investors, and regulators. Greater connectivity, faster processing speeds, improved software, and more integrated information flows meant that managers in all industries were bombarded with new information as it became available — anywhere, anytime. These trends continue to redefine the meaning of organizational intelligence today.

At the time, technology was still in the early stages of exponential growth. Smartphones did not exist and GPS technology was just beginning to become commercially available. The few organizations that experimented with artificial intelligence failed to achieve the desired benefits; as a result, even fewer organizations opted to use AI. Yet firms and entire industries were struggling with the management of information — while a few leaders were exploiting it to their advantage. At the time, I argued that to cope with and take advantage of the acceleration of clock speeds and information flows, organizations had to improve the effectiveness of both their digital and organizational nervous systems, which I measured by what I called Organizational IQ. A key point I made at the time was that the digital and organizational nervous systems were complementary and integrating them was crucial for success.

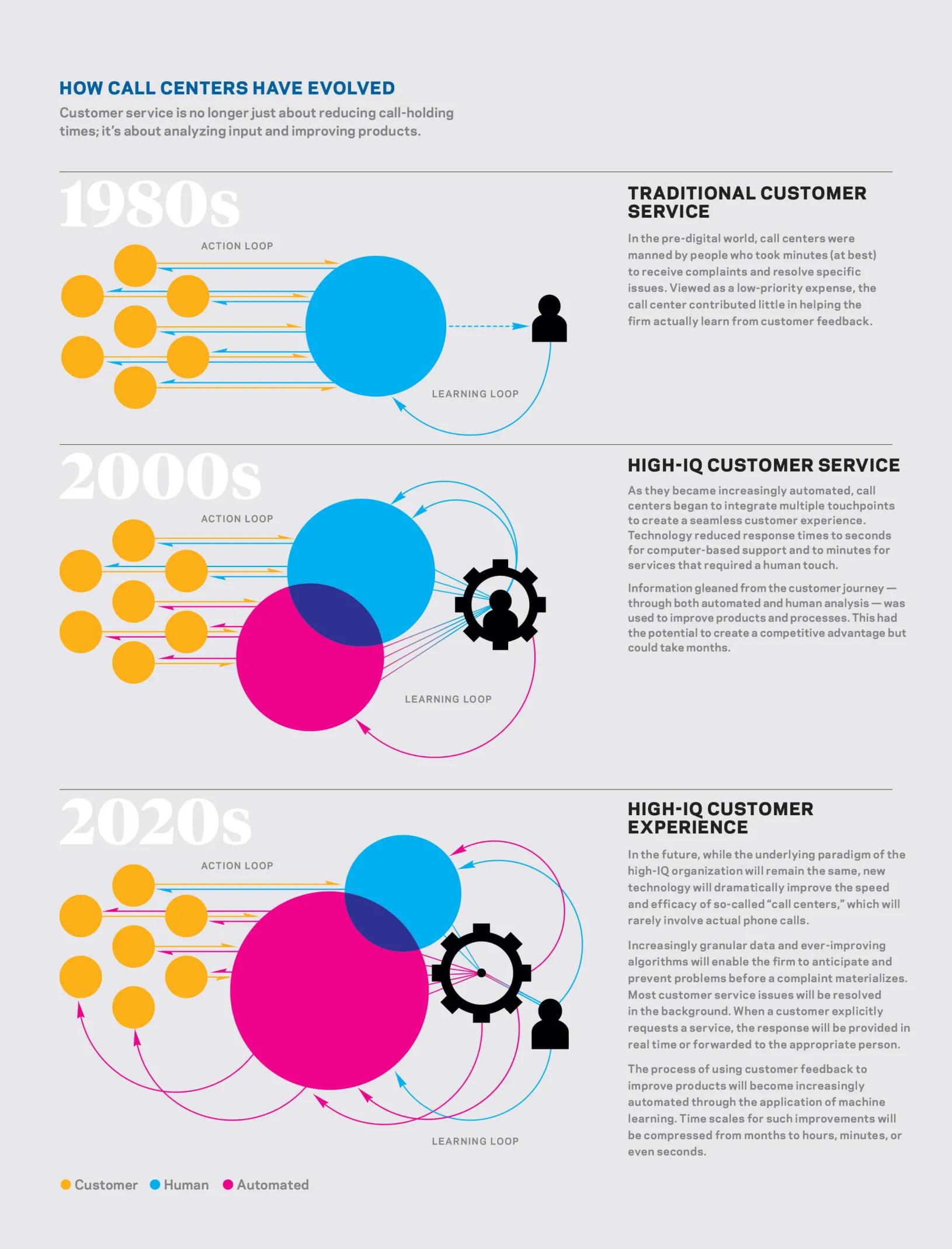

The research that led to the Organizational IQ concept built on an information-processing model of the firm. I viewed the design of an integrated organizational architecture as being analogous to the design of a system of networked computers, with processing being performed by both digital and human information processors. These processors engage in integrated feedback loops whereby they collect information from the external environment and match it with human knowledge and computer-based data to make quick and effective decisions. They move along two feedback loops: an action loop, which translates available information into action, and a learning loop, which uses new information and experience to improve the organization’s perception and understanding of its ever-changing environment.

Building on the analogy to networked computers, the challenge (in simplified terms) is to design an “organizational network” for effective information management. Just like a computer network, the system first needs to have sensors, or receptors, that receive inputs from the outside world and feed them into the network. It also needs processors (human decision-makers and computers) to assimilate the information and quickly translate it into effective decisions, along with design principles to distribute decision-making. The system needs a way to effectively store and share its information so decisions take advantage of its total knowledge base rather than have each decision-maker (processor) limited to its own local data. It also needs to reduce processing bottlenecks — otherwise, it will suffer from information overload, leading to ineffective decisions and late response. Finally, rather than view the organizational network as a stand-alone, self-contained, closed system, it should operate as part of a larger collection of interconnected networks. This extends the concept of interoperability from digital to organizational nervous systems: Systems that were designed for different organizations should be able to work together to accomplish a common goal (or at least a degree of alignment). Along with my research team, I translated these ideas into performance metrics that measured the information-management effectiveness of organizations and found, in a series of papers, that the resulting measure of Organizational IQ was a strong predictor of business success.

If anything, our work from the late ’90s underestimated the importance of Organizational IQ. By now, the key drivers of change have accelerated and their effects have been dramatically amplified. Clock speeds have advanced to the point where actions that once took weeks or hours can now be accomplished in seconds. At the same time, the Internet of Things, advanced analytics, and artificial intelligence have increased the scope, power, and speed of computer-based knowledge management and decision support. As a result, digital nervous systems have moved to the forefront, driving an increasing number of action loops in wide-ranging areas — from automated trading systems to self-driving cars and on to supply chain management. Significantly, digital nervous systems are playing an increasingly important role in the learning feedback loop as well.

We can see these effects in action by focusing on the simple example of customer service (see chart). Traditionally, customer service took place at call centers with an emphasis on solving customer problems quickly and effectively. Agents were evaluated on average hold times on the phone. In contrast, the Organizational IQ perspective views customer service as a competitive differentiator: Not only does it play a role in creating a superior customer experience, but it also serves as a key input to the learning loop that enables the firm to improve customer journeys and product design and to identify new trends. We recommended that, rather than get customers off the phone, organizations increase the value generated by each customer touchpoint, both for the customer initiating the contact and for all future customers. In other words, effective customer service integrates the action loop and the learning loop.

Over the years, leading firms have adopted this point of view. Still, their learning loops were largely human, supported by systems that aggregated and presented information for decision support. Technology is increasingly taking our approach to the next level, with computer-based intelligence playing a key role in both the action loop and the learning loop. Computer-based intelligence improves productivity while reducing the lag between learning and action, aggregates information from multiple sources at the speed of light, turning some organizational problems into engineering problems. It enables the effective delegation of operations such as customer service to best-in-class players, while capturing the benefits of the learning loop.

With the digital nervous system gaining ground, the role of organizational nervous systems is moving away from execution and into business model design, strategy, and control. On the one hand, the increasing capabilities of artificial intelligence create a need for designing and evaluating new business models — something that automation is not good at today. On the other hand, I have argued that business models will evolve to the point where they will be reconfigurable through the intricate interaction of automated agents. We’ll be watching how the boundaries between digital and organizational nervous systems change in the future.

Tricia Seibold

For media inquiries, visit the Newsroom.

Explore More

Is Your Business Ready to Jump Into A.I.? Read This First.

When Social Media and Political Speech Collide