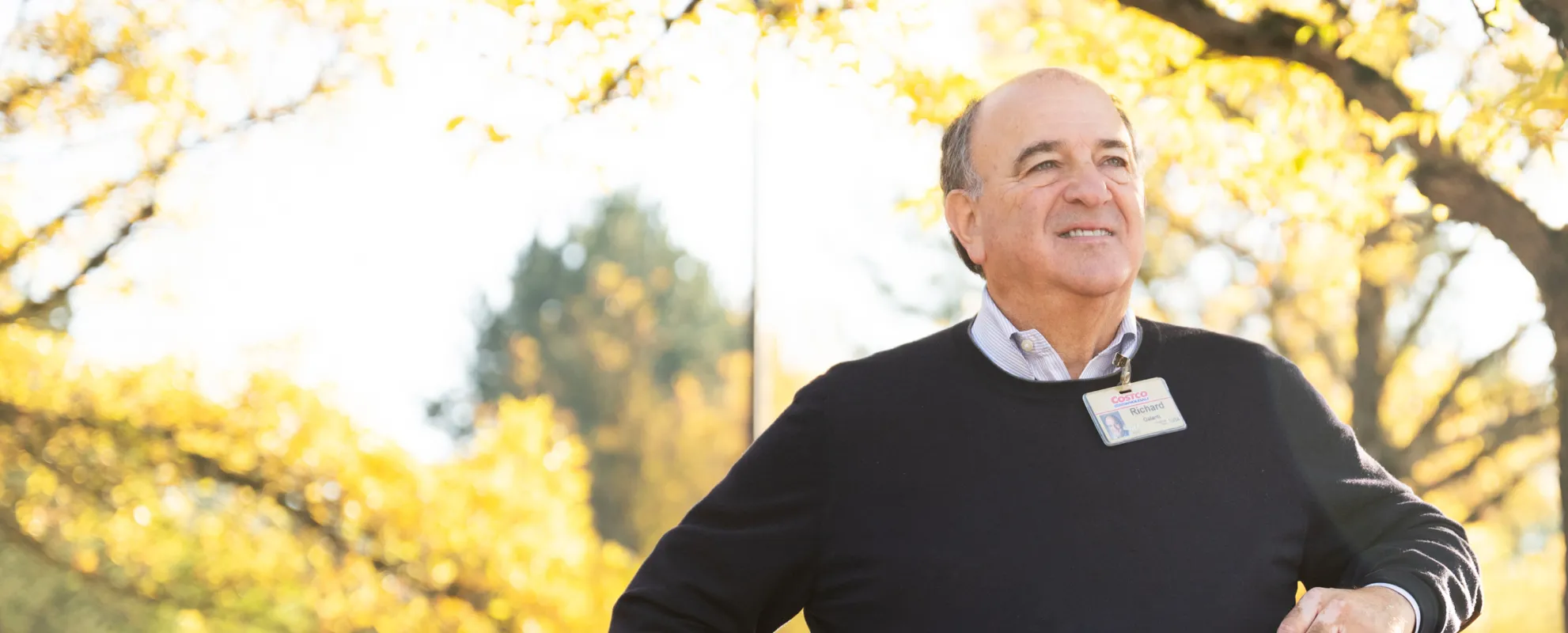

When Richard Galanti, MBA ’82, retired in January 2025 after nearly four decades as the chief financial officer of Costco, some of the warehouse store’s fans panicked. Did this mean the price of its legendary $1.50 hot dog and soda combo was about to go up?

Galanti joined Costco in 1984, leaving a promising future on Wall Street for a Seattle startup with just a few locations and a simple idea: Offer great products at low prices, treat customers and employees well, and build a company that could grow over the long term while “doing the right thing, even when it’s not the easiest option.”

Over the next four decades, Galanti helped steer Costco through its IPO, its merger with Price Club, and its expansion into a global retailer with more than 900 locations. He became the company’s financial anchor, leading more than 150 earnings calls, as well as a quiet enforcer of its core principles, like limiting markups, keeping things simple, and fostering a positive work environment.

Earlier this year, Galanti talked to the CFO Leadership class at Stanford Graduate School of Business, taught by associate professor of accounting Rebecca Lester and lecturers Mitesh Dhruv and Jeff Epstein, MBA ’79. Afterward, he spoke with Henry Lu, MBA ’25, about his journey, from stocking shelves at his family’s grocery store to helping build one of the world’s most admired retailers. And how he helped inflation-proof the hot dog combo.

When you were in your late 20s, you had your MBA from Stanford, a finance degree from Wharton, and you were at a New York investment bank. Why walk away from that path to join a newbie retail startup in the Pacific Northwest?

In the early 1980s, I was working for an investment bank in New York, and the last deal I worked on was the Series A for a startup that was Costco. As luck would have it, Costco was looking for a new CFO, and the co-founders asked me to step in. They liked that I had grown up in a small family grocery business. I used to joke that they liked me because I knew “shrink” wasn’t a doctor — it was inventory loss.

How did growing up in a family that owned a couple of grocery stores shape your approach at Costco?

What I took from that experience was, first and foremost, a strong work ethic. It’s not that I was averse to work, but not all of my friends were spending Saturdays on the job at age 12, or working 50 to 60 hours a week in the summers when they were 14 or 16. But I liked it. I learned how to work. I learned business process. I learned customer service. And that foundation helped me later on, whether I’d stayed on Wall Street or, as it turned out, went to Costco.

Were you ever tempted to move from a CFO to a CEO role?

That’s an easy one. No. Now, there are a lot of people who want to make that jump, but I didn’t. Growing up at Costco in my CFO role, I’ve had an incredibly wonderful journey. I’ve essentially been the CFO from the time we had four locations to now, when we’re a $250 billion multinational retailer. I’ve been through every phase, from private to medium-sized, to public, to large, and larger, and larger.

Costco has developed an extremely loyal customer base — how did you cultivate that?

You start with the founders. Their original mission statement was to provide the best quality goods at the lowest possible prices to our members, our customers, and to do it by following this basic list of actions, in this order: Obey the law, take care of your customers, take care of your employees, and respect your suppliers (be tough but fair). And, ultimately, reward the shareholders.

But going back to that first principle, after obeying the law, the number one tenet is to take care of your customer. From the very beginning, that mission — to deliver the best quality goods and services at the lowest possible prices — was front and center. That was the foundation of everything we did.

What makes Costco’s low prices possible?

The biggest driver is buying power. We only sell about 3,800 SKUs [stock keeping units] — not 50,000 to 1 million. We tell suppliers, “We don’t want six sizes and four colors. We want the two most popular colors in just a few sizes. And make it a multi-pack!”

It makes labor more efficient, too. Think about the labor involved in stocking 2,000 cans in a typical supermarket. At Costco, those cans come in shrink-wrapped eight-packs, stacked 80 to 100 selling units on a single pallet. A forklift operator can place them on the floor in a few minutes.

Every time we save a dollar — whether it’s from better buying power, lower freight costs, or packaging — we aim to give at least 90 cents back to the customer. That way, we make a little more margin while lowering prices even more. I always laughed at the consultants who would come in with frameworks to “maximize pricing efficiency,” meaning how much you could get away with charging. From day one, we had a policy: No buyer could sell below cost or mark something up more than 14% or 15%.

With memberships now driving more than half of Costco’s operating income, how did you think about metrics like membership prices and retention?

It’s funny — about 10 to 15 years ago, a great board member asked, “Have you ever looked at the discounted present value of a future member?” [Costco cofounder and former CEO] Jim Sinegal just goes, “No. Next question.”

We keep it simple. We’ve raised the membership fee eight times, about once every five years, each time by $5 for the basic member and $10 for the executive member. Before we raise the membership fee, we ask ourselves: Have we driven more value to customers to earn that extra $5?

Costco pays some of the industry’s highest wages. What is its philosophy on employees?

We take care of our employees, and they take care of us. Ninety percent of our employees are hourly, and our average hourly rate just passed $30. We offer strong benefits: 401(k), medical, dental, vision. As a result, our employee turnover is 13% overall and just 9% after one year. That’s off-the-charts low for retail, where it’s typically 40% to 60%, and sometimes over 100% in fast food.

When we assign parking spaces at headquarters, they are given out based on when you started at the company. Our new CFO, who started last year, has to park on the third or fourth floor of the garage. You need 10 years at the company before you get an assigned space. Jim set that policy to make a point to show fairness.

From leading a global business with over 900 warehouses, what were some of the most interesting best practices you’ve seen shared across regions?

One example is organic produce. Our Bay Area team started selling organic meat, milk, and lettuce. Then another region tried it. Now we are the largest seller of organic fresh foods in the world.

Another example is international food. With large Hispanic, Asian, and Indian populations across many cities, we’ve done really well bringing in various ethnic food items. Three or four years ago, we put together a team to identify overseas items that would make sense here. One of them was ghee. We sell the heck out of ghee at the best price anywhere.

Costco generates over $10 billion in annual operating cash flow. As CFO, how did you think about capital allocation?

First, we prioritize growth — new warehouses, fulfillment centers, e-commerce, delivery, and manufacturing. Second, we grow our regular dividend, which is now nearly $2 billion a year and has increased about 13% annually since the mid-2000s. Third, we repurchase stock, including offsetting RSU [restricted stock unit] dilution.

We have the good problem of generating more cash than all three of those things require, so we do a special dividend every few years to shareholders, like last year’s $6.7 billion special dividend.

How did you evaluate ROI when building facilities such as the manufacturing plants to support Costco’s iconic $4.99 rotisserie chicken and $1.50 hot dogs?

For our manufacturing plants, we generally look for about 10% cash-on-cash returns. That applies to investments like the $450 million poultry processing facility in Nebraska, our two meat plants in California and Illinois, and our three optical labs that grind lenses for the 9 million pairs of prescription glasses we sell each year.

With our $4.99 rotisserie chicken, if feed prices double overnight, we might lose money temporarily, but we built a plant that processes 2.2 million chickens a week to drive down our cost per chicken.

News of your retirement brought up strong feelings about the $1.50 hot dog. Why do you think shoppers are so fervent about it?

Over time, we kept the same premise: How do we keep lowering the price while improving the quality? At some point, we were selling a huge number of hot dogs. It was an oversized kosher hot dog, and there were two main suppliers: Sinai 48 and Hebrew National. Because of our volume, we were driving up their prices. So we built our own hot dog plant in Tracy, California, which today makes just one item — 200-plus million hot dogs a year. That lowered the price by several cents per hot dog.

I don’t take credit for being the main person defending the $1.50 hot dog and soda. That started with Jim. It just became one of those things where we were determined to figure something out rather than raise the price. I just happened to get a lot of kudos and credit for it on the way out, with people saying, “Oh my God, with a new guy coming in, is the $1.50 hot dog at risk?” But I don’t think it is.

How did Stanford GSB influence your career?

The GSB was, and I assume still is, considered one of the more entrepreneurial programs among the top business schools. The weather’s not bad either, of course.

Looking back at some of the classes I took, a few stand out in terms of shaping how I thought about business. There was the venture capital course. I also remember a seminar course taught by Professor Jack McDonald called something like Investment, Speculation, and Gambling.It was a great class. He brought in a wide range of guest speakers, from Nolan Bushnell, who founded Atari and Chuck E. Cheese, to tech entrepreneurs, and even a professional gambler who was a PhD student at the time.

More broadly, what I remember most about Stanford was the atmosphere. It wasn’t a stuffy place. It was friendly, open, and entrepreneurial. That was the biggest takeaway for me.

Photos by Chona Kasinger