December 06, 2018

| by Martin J. SmithThrough David L. Brunner’s early stint as an engineer, his two years at Stanford Graduate School of Business, and his 34-year career as a capital markets expert at French bank BNP Paribas, one overarching impulse motivated both him and his wife, Rhonda Butler.

“We always wanted to farm in one way or another,” says Brunner, “or at least have access to a rural setting.”

The 1981 MBA graduate had grown up in rural Ohio. Butler, whose banking career paralleled her husband’s, is from the Tennessee countryside. The couple began looking to buy a farm in upstate New York more than 30 years ago. First they looked for places an hour from New York City, then two hours, then three. Nothing was quite right or affordable. Then one day in 1988, Brunner spotted a flier for Asgaard Farm & Dairy in the small Adirondack town of Au Sable Forks — five hours by train and car from New York City. But the $115,000 price tag was attractive.

The 145-acre property — formerly owned by artist Rockwell Kent — included farmland and woods, three silos, a barn complex, and various outbuildings. The structures were in bad shape, and the fields and dairy had been mostly out of production for decades. They bought it anyway.

Brunner and Butler continued their day jobs and raised their daughter in the city, but spent countless weekends over the next 20 years overseeing Asgaard’s rebirth. They repaired buildings and rehabbed the soil and forest. They expanded the farm to 1,434 acres and built a solar energy system that now supplies 85% of the farm’s power. When their daughter left for college in 2009, they began the transition to full-time farmers.

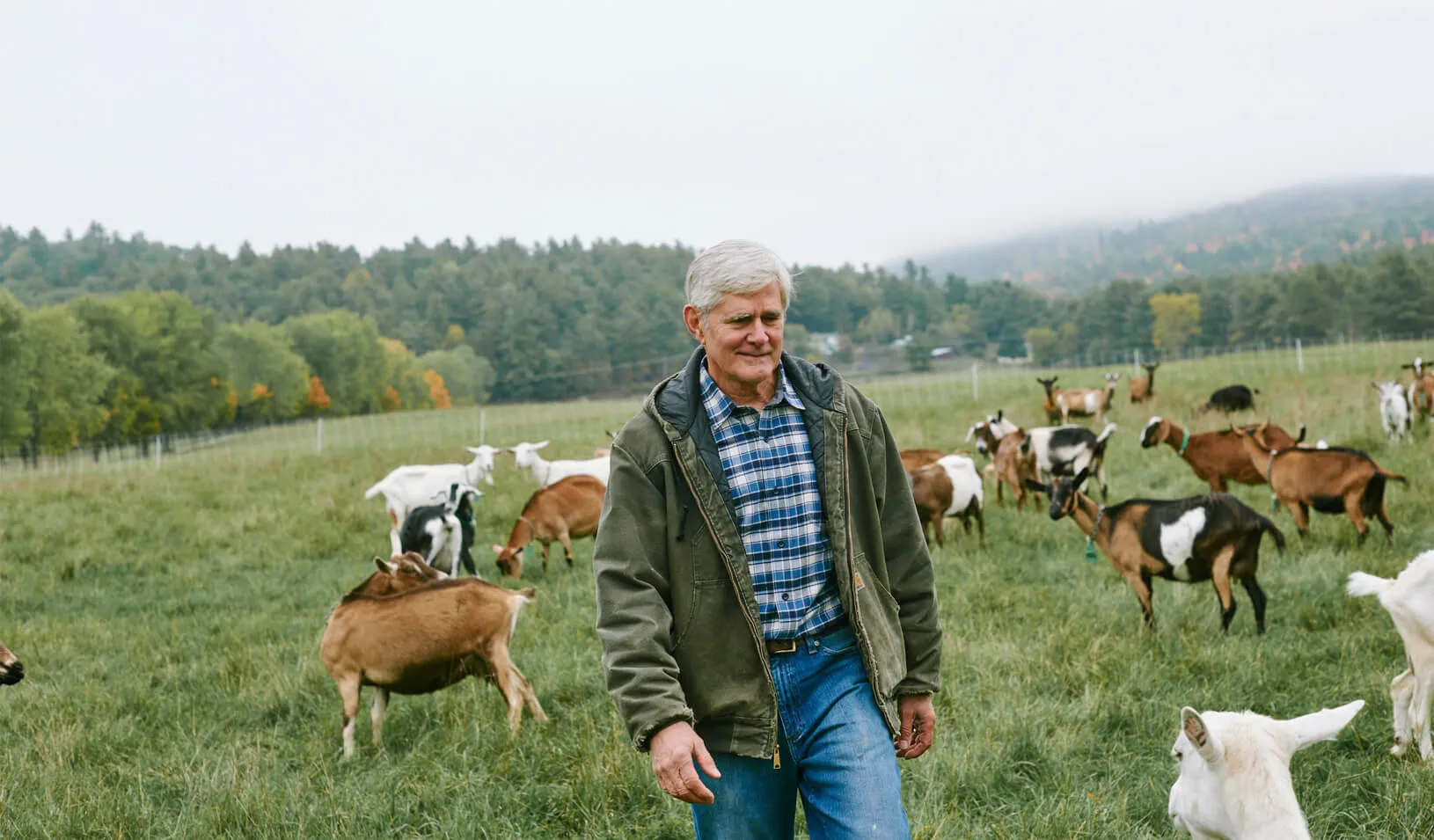

Today, Asgaard is a model of sustainable small-scale farming. Its milking goats produce cheeses that have won several awards from the American Cheese Society and been featured in Gourmet magazine. We spoke with Brunner about his slo-mo journey back to the farm.

You started your professional life in 1977 as a field engineer for a construction company. What drew you to Stanford GSB?

My dad had always told me that engineering was a great place to start, and I was good at math and science. I applied to several business schools and got into Stanford, but they suggested I go out and work for a couple of years before entering the program. That gave me an opportunity to work for Turner Construction, a national company. I had a great experience there, but I was still interested in business school. I entered Stanford in fall 1979.

How did you end up in banking?

I did a summer internship with Warburg Paribas Becker, and that turned into a job. I liked the financial world and saw it as an opportunity to learn and see other parts of the world — another thing my father had encouraged me to do. I ended up in banking for more than three decades with the same company.

What shared values led you and Rhonda to buy Asgaard Farm?

Our motivation was quite simple. We both grew up in rural communities where farming was strong and were looking for a farm that could be made to work again to return to these roots.

Why the slow approach?

We always knew it would take a long time and were in a position to take that time. We needed to spread out the costs. Also, restoring soils takes years, and restoring forest property takes decades. So we put no pressure on ourselves to move quickly. We both had great careers at nice institutions and were raising our daughter in New York City. For the first 15 years we owned it, we basically just cleaned it up. As we were here longer, we thought about how to put the operation back together and make it viable.

What was your biggest challenge?

When you just graze and take hay off fields, it’s like mining the land. It depletes the soil over time. So we went into an organic grain rotation, a three- or four-year cycle of wheat or rye then hay, using lots of compost and organic materials. And over the years, we brought the soil back. Growing crops was something that didn’t require us to be here every day.

But how do you turn a rundown farm into a viable business?

No one is going to get rich on a small-scale farm. The question is: What is your objective? In financial terms, it has long been our aspiration and challenge to make it economically sustainable. If we can’t make it work, it can’t sustain itself. But we think it’s possible.

Are you in the black now?

We’re almost there, and most of our farming activities are contributing. We’re diversified beyond the dairy, offering grass-fed beef, pork, and poultry products.

Any similarities between overseeing capital markets for a large bank and running a small farm?

Yes. Just as in capital markets, we focus on managing risks. Risks in farming are equally challenging — weather, equipment failure, facility downtime, animal health, predators, regulatory risks, commodity price risks. Our diversified model of farming is a hedge against commodity risks, because we produce cheese and other consumer products. You don’t see the kind of fluctuations in prices with retail products as you do with commodity products.

Do you feel you were ahead of the curve in 1988 when you focused on small-scale farming?

We appreciated the virtues early on and wanted to farm and ended up being part of the resurgence in small-scale farming in recent years. We welcome it, because the support for our products from restaurants, along with interest from the general public, has all been a great help.

You’ve said you’re in this because farming is “good food, good business, and great for the environment.” Are those the core values you were pursuing when you bought the place?

Those are the three essential points, yes. You can make really great food on a small-scale farm, and more chefs are appreciating how important it is to have farm-fresh products. And there are well-recorded health benefits of farm-grown foods. It’s also good for conservation, because farmers have been depleting soils for centuries, and small-scale farming practices can restore these soils and sustain the landscape. Third, these small farms are good for local economies. We create jobs and support local businesses. All those things mutually reinforce each other. That’s not to suggest we can replace large-scale agriculture, but small farms can play an important role.

Do you make money from the farm in ways other than agriculture?

We have around 1,000 acres of sustainably managed forests. That’s a contributor in years when we harvest logs and firewood. In addition, we have a couple of long-term rental properties that came with the farm and a short-term farm-stay program that brings visitors who stay for anywhere from a weekend to several weeks. Finally, we make long-term investments in agriculture, renewable energy projects, and new regional businesses.

Does that put you in the marketing business as well?

Part of our mission is to restore the connection between people and their food, and you do have to pay attention to customer development, service, and logistics. Social media (especially Facebook and Instagram) helps with getting our message out. We also host events, including five this summer that brought more than 4,000 visitors to Asgaard. That’s a way to both develop our customer base and fulfill our mission. It all helps. Profit margins are very thin, so you have to be the best operator you can.

Any ancillary benefits for your family?

You have to be joking. Last night, Rhonda and I were deciding whether to have dinner or just graze. We stopped by the garden and got a couple of ears of corn and some lettuce, then stopped by the freezer room and picked out steaks, grabbed some cheese from the cooler, and came back and ate. Now if that’s not wealth, I don’t know what is.

Any regrets?

I guess we don’t go on as many vacations as most people. But to be honest, I like being here. I like the intellectual challenge and the daily work.

Any lessons from Stanford that have proved especially helpful?

I had an organizational behavior class where a visiting professor from Brigham Young passed along the strong message that you have to rely on yourself to figure out what to do. And above all, be passionate about what you’re doing.

For media inquiries, visit the Newsroom.