April 01, 2015

| by Mark LeslieSuccessful enterprises have a cycle of life. Startups build a product or service, enter the market and attract customers. Once they’re over these initial hurdles, they enter a growth phase, rapidly increasing their revenue and market share with big gains year-over-year. They continue to work on their product, fine-tuning it as revenue starts to flatten and margins stabilize at lower but still attractive levels.

As these companies mature, growth slows even more, eventually flattening out — yet operational expenses continue to climb as they strive to compete with new players in the market. Finally, unable to keep up, burdened with bloated budgets, companies spiral into negative growth, marked by layoffs, high burn rates and eventual bankruptcy or liquidation.

This paints a pretty bleak picture — especially if one considers the inevitability of this pattern — but it’s important to note that this cycle plays out over drastically different time lines for different companies. Many successful companies have prolonged their relevance for decades, and some for over a century. Technology companies are just like “real companies” except that the cycle is shorter so everything happens faster.

First Round Review

The key to enduring growth is strategic transformation. When a company forgoes the “good life” of maturity, controlled growth and market leadership and is willing to take on the risk of transformation in the face of existential risks, it can achieve new levels of growth and extend its horizons.

The ability to do this is largely dependent on the type of leader charting the course. Most leaders fall into one of two categories: Opportunity-Driven or Operationally-Driven. As you’ll read below, there are incredible advantages to having an Opportunity-Driven leader at the helm to drive transformation. Operationally-Driven leaders, while excellent at driving efficiency and predictability, may place the company at long-term risk as it merely stays on track on the Arc of Life.

One of the largest and most influential software companies in the world, Oracle was originally founded as Software Development Laboratories in 1977. Between then and 1982, the company searched for product market fit, eventually determining how to commercialize its relational database system for enterprise companies. That’s when it was officially named Oracle and entered growth. But when most early employees recall what gave the company its early competitive edge, they point to CEO Larry Ellison.

Bruce Scott, co-architect and co-author of the first three versions of the Oracle database put it this way: “I’ve thought a lot about why Oracle was successful … It was really Larry’s charisma, vision, and his determination to make this thing work no matter what. I can give you an example of his thought processes: We had space allocated to us, and we needed to get our terminals strung to the computer room next door. We didn’t have anywhere to string the wiring. Larry picks up a hammer, crashes a hole in the middle of the wall and says, ‘There you go.’ ”

This description of Ellison as a risk taker who saw quick, unorthodox solutions to keep things moving calls attention to one of most important characteristics of enduring companies: their CEOs are opportunity-driven leaders. You can identify this type of leader by their ability to not just see the future but seize it, their comfort with unconventional strategies, and their acceptance of bold risk. They don’t measure their success by rankings, quarterly earnings or liquidity events. They have a more grandiose vision to change the world, build a global brand, upend an existing industry.

This type of leader drives change with charisma and force of personality that can be better described as gravitational pull than a management style. Companies need this type of figure to justify unusual, unintuitive and risky shifts in direction. It’s not enough for them to convince people that they are right, or to follow them down a different road — they make any other choice or destination seem untenable.

When Oracle got its start building portable, scalable database systems, there were many other startups in the market trying to do the same thing.

Most of them made their competitive edge about more features and better performance, while Oracle focused on an industry-wide platform — making its database compatible with as many computing platforms as possible (IBM, Digital Equipment, many flavors of UNIX, NT, etc.). By the mid-1980s, its software could be used on 80 different vendor systems, enabling it to be used by almost any enterprise.

Oracle’s versatility distinguished it as the choice for application developers and resellers because it also gave them access to much larger markets.

As the need for applications grew, so did Oracle’s top line. By 1987, it was the world’s largest database management company with revenue over $100 million and 4,500 clients in 55 countries. Spotting the source of this success, Ellison brought in Jeff Walker, founder of one of the top accounting application development firms, and charged him with building an applications division within the company.

He did this even though Oracle had many more years of steady growth and healthy margins to harvest from its database business. He did this even though Oracle’s own applications wouldn’t take off until the 90s. Most importantly, he did this in the face of the fact that the application vendors (i.e., People Soft, SAP, etc.) who “pulled” through his product would now see Oracle as a competitor with an unfair advantage instead of as an enabler. In so doing, Ellison put his existing market at great risk. He saw the opportunity for transformation and used the momentum the company had during its growth phase to make it possible.

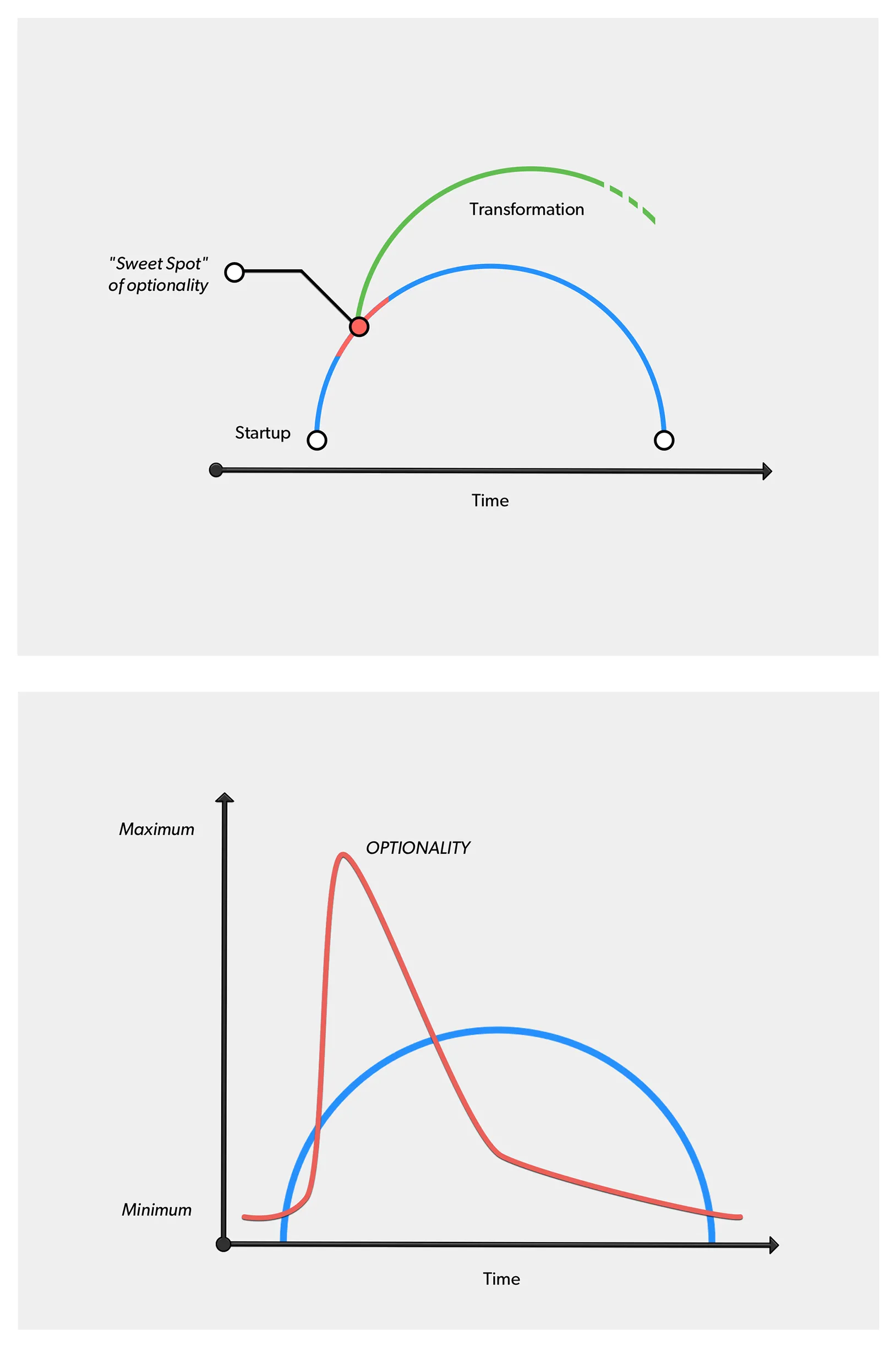

There’s a moment along the corporate Arc of Life between growth and maturity that allows for Maximum Optionality — that’s the sweet spot for change and renewal. How can you see this moment coming? Here’s what it usually looks like:

First Round Review

- You’re finally out of the startup phase and no longer have to worry about scarce resources or traction.

- The organization has achieved a measure of stability — the future looks bright, revenue is climbing, and the business model has gelled.

- You just reached a point where you have the talent, money, and market influence to do something new while maintaining and growing the core business.

- The wind is at your back!

As a startup approaches the crest of its growth curve, its leader has a choice to make: Will the company take advantage of its momentum and initiative to steer into uncharted waters (a new line of products, a new business category, a new industry)? Or will it continue along the well-marked path squeezing as much as it can out of its existing business?

When things are going well, most leaders are reluctant to take significant unnecessary risks in favor of market dominance. In doing so, they fail to see what lurks on the other side of “success” — plateau and decline. Even as ecosystems shift around them, they hold onto what they know and what has worked before instead of innovating to fit customers’ new expectations.

In stark contrast, Opportunity-Driven leaders see the sweet spot of optionality not as a risk but as a springboard to hurtle the company to the next level. Their vision charts the course the company needs to take, and their conviction in the choice compels their core employees to commit to the journey even if the outcome isn’t immediately clear.

In retrospect, the need for innovation can seem obvious, and even easy. But deciding to take this road — branching away from the traditional Arc of Life — is anything but.

At the time, Oracle branching into the applications business was a radical move. Not only did the initiative surpass the scale of anything the company had attempted, it also declared war on the application resellers whose livelihoods depended on its software — essentially forcing them to choose between Oracle and its competitors and threatening the very revenue stream that financed its new applications business.

Despite these many challenges, Oracle was able to make room in the market for its own application products. Still, the amount it invested in the area was considered by many to be distracting and reckless, particularly when the company was still capturing massive year-over-year revenue growth from its core database business. What they didn’t see was that license revenue from this business was starting to flatten at a quicker and quicker pace. While not immediately visible to people even inside the company, applications represented Oracle’s next cresting wave.

One barrier remained in the company’s path: SAP, the 800-pound gorilla in the market producing client/server-based applications for enterprise. There was no way around it. Oracle couldn’t take down SAP to become the number one provider of enterprise apps unless the landscape changed. So it took another big gamble on top of its already risky app strategy and built a new landscape for the industry.

In his biography of Oracle and Ellison, Softwar, Matthew Symonds described this flashpoint: “To the horror of many colleagues and customers, [Ellison decided] to abandon all further development of client/server-based applications and concentrate the entire firm’s engineering effort on building for the Internet.”

Oracle’s sales force bristled and customers fled. But Ellison wouldn’t be deterred from this brand new direction. “They were mistaking the present for the future,” he said. “Client/server was dead and the people in the room would figure that out at the funeral.” He knew Oracle couldn’t wait to change course.

Other companies were building web-based applications at the time, but Oracle was the only one that went all in to wholeheartedly pursue an internet strategy at the risk of its entire business. Ellison was quoted at the time: “If the internet turns out not to be the future of computing, we’re toast. If it is, we’re golden.”

In 2000, the company introduced the Oracle E-Business Suite, the first fully-integrated, comprehensive suite of business applications for the enterprise. It obliterated the need for expensive system integrations and earned immediate popularity for its ease and efficiency.

Oracle has remained committed to strategic transformation. After 25 years of zero acquisitions, it turned its firepower on consolidating the enterprise application market with massive acquisitions. First came Peoplesoft in 2003 for $5.1 billion in the Valley’s first ever hostile takeover. BEA and many others quickly followed. Oracle eventually rolled up all of its competitors except for SAP, finally assuming market dominance.

Its most recent bet was the acquisition of Sun Microsystems to become a fully integrated systems supplier. Not all bets taken are won, and it’s likely too early to tell on this latest one. (It’s also worth noting an interesting side-bet. Larry Ellison is the principal investor and majority owner of NetSuite in the same business on the lower end of the marketplace).

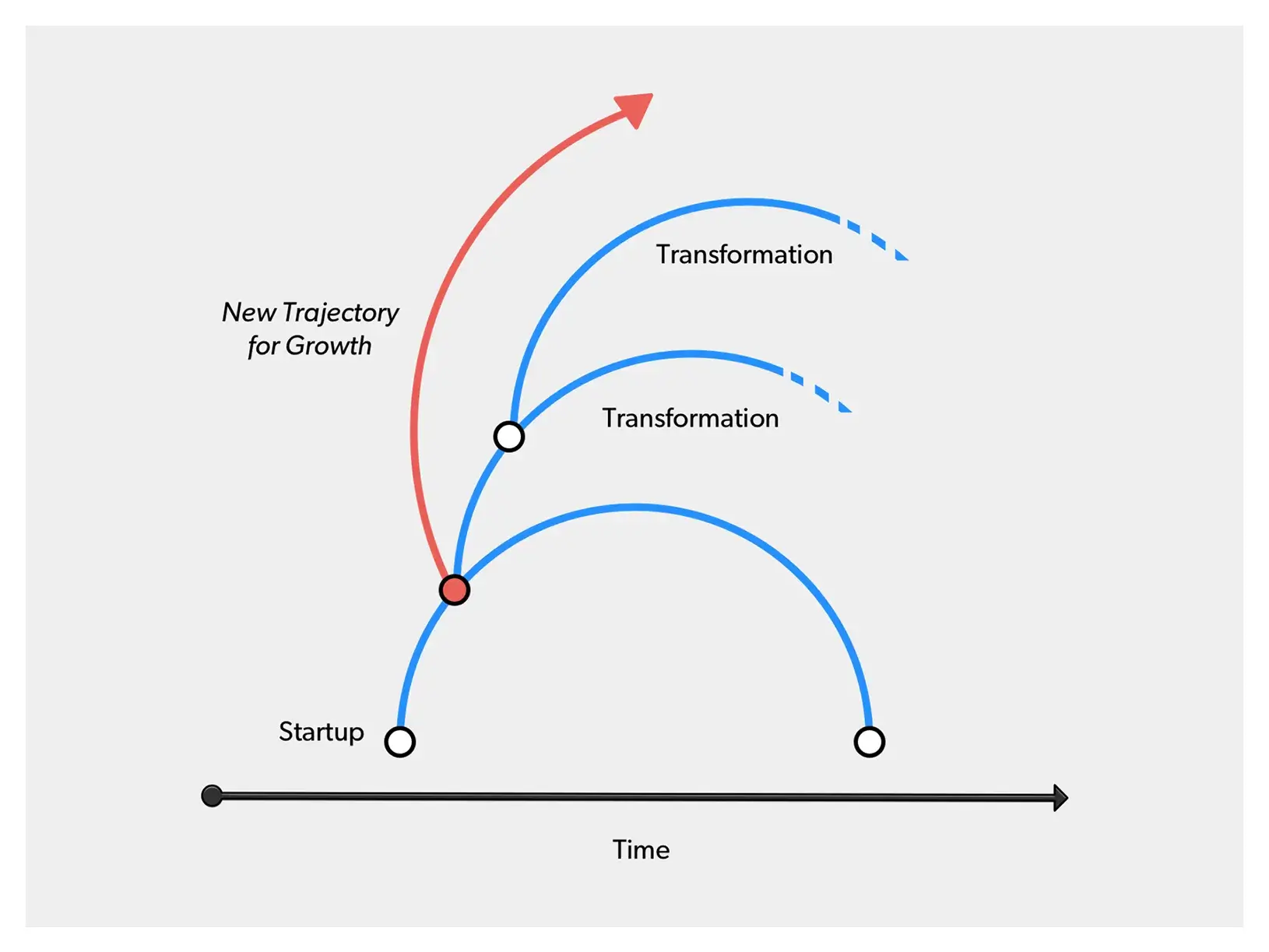

Oracle’s dogged pursuit of this position in the space illustrates one of the more important lessons of the corporate Arc of Life: An organization’s transformations will inevitably vary in scale, time to execute and impact on the business.

But, when taken together, a series of successful transformations — big or small — will meld over time into an overarching story of transformation and extended life expectancy.

Here’s how that looks:

First Round Review

And here’s how it looked for Oracle:

First Round Review

Another example of a company buoyed by many transformations is AmazonAmazon — with Jeff Bezos, another truly opportunity-driven leader spearheading change. Over its 20-year history, Amazon has taken advantage of sweet spots of optionality to cover new ground and develop products far outside its core competency, all while shaping the way consumers buy and retailers sell online.

One of Amazon’s biggest points of transformation was the launch of zShops, the platform that enabled small businesses to set up their own virtual storefronts and sell products through the site. While it was not a game-changer on its own, it ultimately led to the creation of Amazon Web Services, leveraging the company’s internal software architecture to provide other businesses with affordable cloud services. In this case, a huge, successful detour from the business sprang from a smaller venture. Web Services is now growing at a faster rate than Amazon’s consumer-facing retail operations.

The takeaway is that not all transformations have to change the world. Some may just make a dent or open a door. It’s virtually guaranteed that not all attempts at radical change will succeed. It’s up to the opportunity-driven leader to weigh the risk of failure against the risk of reward. Does your company have the financial fortitude, employee loyalty, and broad support it needs to survive a failed attempt at metamorphosis? Or are the consequences simply too dire? Sometimes a company needs to make the leap even if the latter is true.

On the flip-side of this narrative, you have the many hundreds if not thousands of companies that have gone the way of the woolly mammoth because of their inability to adapt.

Oracle and Amazon are far and away the exceptions to a much storied rule. In almost all cases, the CEO dutifully leads their company down the path of metrics-focused execution and reliable growth. Along the way, they either intentionally bypass sweet spots of optionality or miss chances to bring new ideas into the company.

These leaders are more driven by operational excellence and efficiency — becoming the foil to Opportunity-Driven leaders. They’re motivated to achieve established metrics and conventional definitions of success.

This type of person is well-suited to run the show during the period in a company’s life when seamless execution is needed after major transformation. They may even be skilled at articulating a vision for the future. But that vision is more likely to be conservative, smaller in scale, less risky. Ironically, these types of CEOs are revered by Wall Street as their companies perform reliably quarter after quarter. That is, until they fall off the growth curve and have no place to go.

Even when Operationally-Driven leaders see a sweet spot for transformation, they will probably fail to seize it — they don’t have the same tolerance for risk, the ability to stand up to naysayers or the charisma to pull an organization along with them. Vision doesn’t matter if a leader doesn’t have the audacity to pursue it. The Operationally-Driven leader may excel at trekking a marked path but does not wield a machete to create a new one.

Under this type of leadership, a company can enjoy many good years climbing toward maturity. But failure to create new growth curves when the moment is right puts even the most successful companies in history at risk of extinction.

Nokia is a prime example of a company that has historically been in the lead but is now struggling to stay afloat. Like Oracle, the company built its success on early transformative leaps. A lot of people don’t know that it started as a paper mill in Finland in 1871, and is one of the best examples of a company that has changed perfectly with the times.

When cars became more prevalent, Nokia evolved into a rubber manufacturer making everything from tires to rain galoshes. When telephones started to enter the mainstream, it became one of the first telecommunications companies, developing radio telephones for the army. This attitude continued into the 1980s when it launched the first mobile car phone. By the 1990s, it was the global leader in mobile phone technology.

Now, with Apple and Samsung splitting the mobile market between them, Nokia has been losing market share steadily for the last four years. It simply stopped innovating. Its leadership stopped taking huge bets, and the lack of a new growth curve is only now becoming apparent — particularly with the sale of its device business to Microsoft in 2013. Unless Nokia’s leadership is willing and able to make a transformative leap of the same size and scale that it did in its early history, this could be the end of the line.

Their names are legion: Kodak, Blackberry, Digital Equipment, Data General, Silicon Graphics, Sun Microsystems, Yahoo, AOL, and so many more. And there is a new generation of iconic companies that are now at existential risk as their fortunes have faded in the face of industry disruption: IBM, Cisco, EMC, NetApp, Juniper, Dell, and the list goes on.

No matter what excuses are made or exceptions declared, it’s the rule that companies at one time viewed as clear winners will ultimately experience the threat of decline and extinction at the end of the Arc of Life. No organization is immune to this fate. Only a select few have demonstrated their ability to undertake enough transformative shifts to extend their life decades beyond their competition.

Although a company’s trajectory may be influenced by any number of factors — market forces, political climates, economic spikes, and dips, popular trends — it’s arguable that nothing is more critical than the vision and path set by its leader.

To ensure long-term success, boards of directors and investors should seek out and reward CEOs who are Opportunity-Driven leaders, willing to punch holes in walls, and embrace new, often dangerous risks before the road ahead starts to flatten and becomes more certain. As promising and profitable as good valuations and strong market positions may appear, they do not guarantee a company will endure for the long haul.

It is sad but true that there is no place to rest. There is no finish line.

Mark Leslie is a lecturer at Stanford Graduate School of Business where he teaches courses in entrepreneurship, ethics, and sales organization. He is also the managing director of Leslie Ventures, a private investment company, and serves on the boards of two public companies, six private companies, and three nonprofit organizations. Prior, Leslie was the founding chairman and chief executive officer of Veritas Software. He tweets at @mleslie45. Sara Rosenthal, a case writer at Stanford GSB, contributed to this article.

This piece originally appeared on First Round Review and is republished with permission.

For media inquiries, visit the Newsroom.