May 04, 2015

| by Deborah PetersenMitt Romney may be best known for being the Republican candidate who ran against Barack Obama in the 2012 presidential election. But even though Romney didn’t become America’s CEO, he has led companies, organizations, and one state government. He was CEO of Bain & Co. and later cofounded Bain Capital, led the 2002 Salt Lake City U.S. Olympics Organizing Committee, and was elected governor of Massachusetts in 2002.

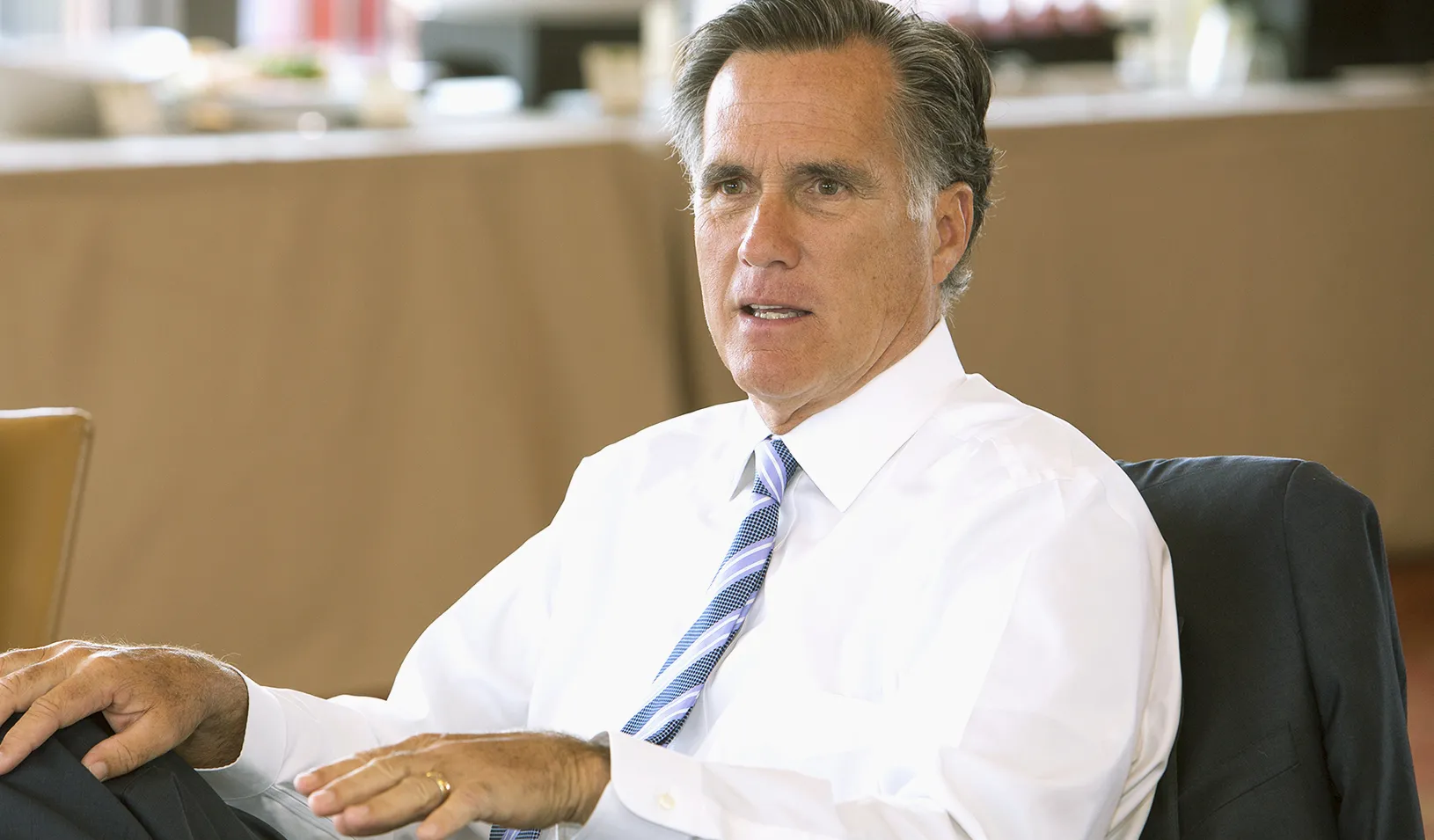

Mitt Romney spoke to the Stanford GSB community in April. | Stacy H. Geiken

Romney mixed self-deprecating humor with leadership advice during a recent View From The Top talk at Stanford Graduate School of Business. A friend, Romney says, once told him that there are two kinds of people: those who have plenty of clarity about what makes them an effective leader and those who have “no clue why they are a leader.” The friend counted Romney in the latter group. Still, Romney shared plenty of leadership advice with the students who gathered to hear him during the April talk.

Take a Break

Romney says that when he attended college at Brigham Young University and then Harvard for a dual law and business degree, “I was convinced I would flunk out.” That insecurity propelled him to study “all the time.” He felt guilty when he took time off, but he knew the pace was not sustainable. A member of the Mormon church, Romney drew from his faith to find his solution. He decided to make Sunday a day of rest. “A few of those decisions early on shaped my life,” he says. In later years, after he was married and had children, he tried to “close his briefcase” when he was at home in the evenings. “If you take a block of time off for yourself, you may be more productive,” he says. “I don’t think it hurts to have more in your life than work.”

Do What You Love

As a young man, Romney was not sure what he loved to do, but he quickly learned what he did not like to do. Growing up outside of Detroit, where his father was the CEO of American Motors Corp., “I fully expected to work for a car company.” But when he tried it briefly, he hated it. “[It was] not at all like what I imagined,” he says. Then, he took a summer job at a Boston consulting firm. “It wasn’t a great analysis to say, ‘This is the next step in my career.’ I just enjoyed it,” he says. “I like consulting because I am oriented to solving problems,” he says. Finding what you enjoy doing is more important than strategically seeking out what career will make you the most money, he says.

Know Your Values

As the youngest in his family by six years, Romney was still living at home when his siblings had left for school and other places, and therefore he had the opportunity to spend time alone with his father, including accompanying him to work occasionally.

“I got to watch how my dad interacted with people not realizing that I was learning.” It is why, he says, that respect for others is ingrained in him. “I don’t try to treat people with respect; I respect people,” he says. “I think it’s important to know what your values are.”

Encourage Dissent

Romney gets worried when he’s leading a meeting in which everyone is in agreement on an issue from the start. It is risky, he says, to make a decision unless the dissenting side has been presented and dissected, he says. In some cases, he has postponed making a decision until his team comes back with the reasons for not doing something. It’s important, he says, to have a mutual exchange of ideas before taking action. “If we can come up with the right answer, I don’t care whose idea it was,” he says.

Complement Your Weaknesses

“By and large, people don’t overcome their weaknesses,” says Romney, who prefers to accentuate and build the strengths of others by hiring people who complement each other’s skills.

Learn from Strategic Mistakes

It’s a fact of Republican life, Romney says, that few minorities vote in GOP primaries. And when seeking the Republican nomination, Romney says, his campaign focused mostly on white voters. Then, after he won his party’s nod and start visiting minority communities, residents in those places wondered “‘Where have you been?’” he says. “I think that was something we missed in our strategy sessions.”

Define Yourself

One of the big risks, especially for politicians, is that their challengers will define them. When he ran against Ted Kennedy in 1994 for Kennedy’s U.S. Senate seat, he sought advice about how to handle attacks by the Democratic incumbent who ultimately defeated him. Romney was told, “If you are explaining, you’re losing.” You never respond to attacks, you just attack back, he says. It’s not necessarily the best system, he acknowledges. Most of what people see of candidates are small sound bites delivered in political ads and debates. In the aggregate, the exposure voters have to a candidate is minimal. “You spent more time with me now” than during the entire presidential campaign, he told the audience.

“I don’t know how [politicians] can do a better job of describing and showing who we are.”

Have a Higher Power

Romney frequently mentions his faith in God and the central role religion plays in his life and work. He knows not everyone shares his religious views, he says, but he thinks everyone can benefit from believing in some brand of higher power. “I believe if you believe in something greater than yourself, you will be more successful.”

For media inquiries, visit the Newsroom.