How to Get Beyond Talk of “Culture Change” and Make It Happen

Experts outline their roadmap for intentionally changing the culture of businesses, social networks, and beyond.

February 20, 2024

Calls for cultural transformation have become ubiquitous in the past few years, encompassing everything from advancing racial justice and questioning gender roles to rethinking the American workplace. Hazel Rose Markus recalls the summer of 2020 as a watershed for those conversations. “Everybody was saying, ‘Oh, the culture has to change,’” says Markus, a professor of psychology at Stanford. “It was just rolling off everybody’s lips in every domain.” Yet no one seemed to know what exactly that might entail or how to get started.

As they followed these discussions, Markus and her colleagues Jennifer Eberhardt and MarYam Hamedani wondered what they could contribute at this moment as experts with years of experience studying how communities and organizations can turn the desire for change into something real. “Culture is all around us, but at the same time, it feels out of reach for a lot of people,” says Eberhardt, a professor of organizational behavior at Stanford Graduate School of Business and of psychology in the School of Humanities and Sciences.

Markus and Eberhardt are the faculty co-directors of Stanford SPARQ, a “do tank” that brings researchers and practitioners together to apply the lessons of behavioral science to combating bias and disparities; Hamedani is its executive director and senior research scientist. Recently, along with associate director of criminal justice partnerships Rebecca Hetey, they published an evidence-based roadmap to intentional cultural change in American Psychologist. They hope, Hamedani says, to illustrate “a path forward and to make the claim that culture change is possible.”

Stanford Business spoke with Eberhardt, Hamedani, and Markus to discuss the complexities of changing a culture and how leaders and readers who are committed to doing things differently can get started.

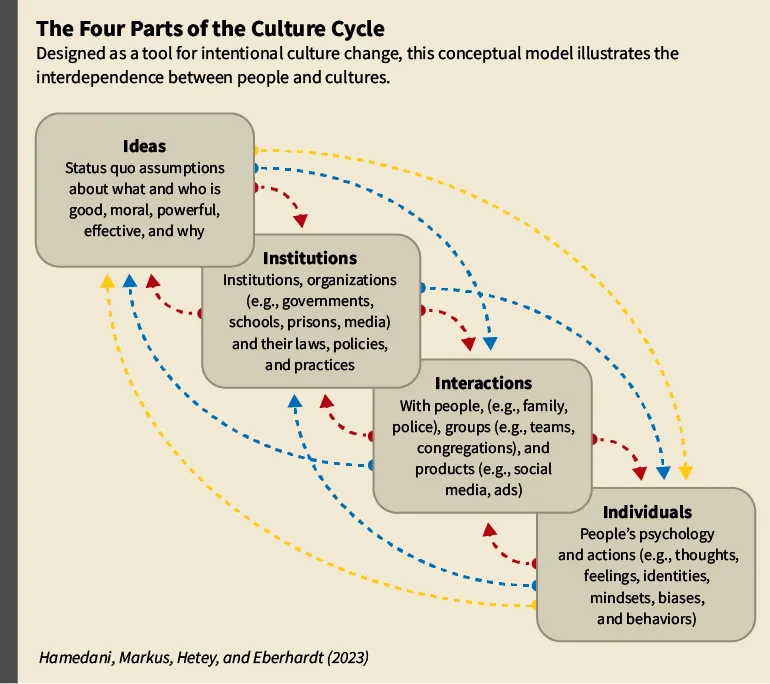

You start the paper with the “four I’s,” categories you believe can help people map their cultures and see where there might be tensions or mismatches. Using organizational cultures as an example, can you take us through those?

Hazel Rose Markus: There are the ideas, the big ideologies that are foundational for any organization: This is how we do things, what’s good, and what we value. Then the institutional parts, which are the everyday policies and practices that people use to do their work. Often, those have been in place for a long time and people tend to follow them as if they were the natural order of things. Another I is the interactions, which have to do with what’s going on in the office every day, in your relationships with your colleagues, with the people you supervise, with those you answer to. And finally, the fourth part is your own individual attitudes, feelings, and actions.

Is there a way to sum up your roadmap for changing culture?

MarYam Hamedani: The first key idea is because we built it, we can change it. There are many forces out there that are out of our control, but the societies we build and pass on — the organizations, the institutions, the way we live our lives — those are things that are human-made. And so we should feel empowered by that inheritance because that’s the thing that gives us the ability to make change.

The second part is that culture change usually involves a series of power struggles and clashes and divides. You have different groups that feel like they’re winning and losing. There’s a lot at stake for people. It’s important to try to have strategies to deal with that.

Finally, culture change can be unpredictable and have unintended consequences. Yet the dynamics can also follow patterns — for example, backlash happens. Timing matters. So you have to be nimble; you have to realize that cultural change never ends. It’s a sustainable process that you have to stay on top of, and that’s OK.

Markus: Yes, changemakers can’t be discouraged when they see backlash. Also, we want to help people remember that yes, they are individuals, but they are also making culture through their actions. How our everyday actions can contribute to a larger culture and to its change is something I think we are less likely to think about in our individualistic system.

Hamedani: Right. We are individuals and in charge of our own behavior, but then we are powerful as a group.

Markus: With each other, what are we modeling? What are we putting our efforts behind? What’s the impact on the workplace?

Your paper was written with the problem of social inequality in mind. What message does it have for business leaders?

Jennifer Eberhardt: As business leaders, you have both a lot of power and, I think, a lot of obligation to understand the workings of culture. You have the power to pull the levers of change. You dictate what the social environment is like for everyone else. So you have a heavy hand in creating and sustaining the culture that is there — but you can also have a heavy hand in changing that culture for the better.

Markus: When culture change is on the agenda, you often hear leaders — like those in the tech industry — and the first thing they often say is, “OK, I’m going on a listening tour.” But you rarely hear about what they’re going to listen for or what they heard from those who report to them or how they’re going to put that into action.

Listening is valuable because it conveys empathy, but it is useful to listen specifically for what people understand as the important values of our organization, the undergirding ideas. What are we about? What are we trying to be as an organization? And, very importantly, do our policies and practices reflect these ideas and values and our mission? We can say we’re about one thing or another, but how is it materialized? How does it show up in our everyday work? Is there a general alignment across the four I’s of the culture?

You worked with Nextdoor on a project to change its culture. How did that go?

Eberhardt: They reached out to me and other researchers trying to figure out how to curb racial profiling on their platform. In the tech industry, people are focused on building products that are easy to use, products that are intuitive, so that users don’t really have to think too hard. But those are also conditions under which racial bias might thrive. So we encouraged them to slow users down, to increase friction rather than trying to take friction away.

They accomplished this by creating a checklist for users to review before posting on a Nextdoor forum. The first thing they ask people to consider is that a person’s race is not an indication of their criminal activity. And also when they describe a person, you don’t just describe their race, you describe their behavior. What are they doing that seems suspicious? Nextdoor found that just simply slowing people down in this way, based on these social psychological principles, they were able to reduce profiling by over 75%.

They were trying to solve for something at the interaction level. What they could change was what the experience was like for users at the institutional level. Just by making these simple tweaks to the platform itself and how they presented information, they changed these negative interactions that were taking place that then could also shape people’s ideas about race.

You also talk in the paper about the example of investment firms struggling to become more diverse.

Markus: Typically this has been the territory of white men with economics degrees from Harvard, Yale, Stanford, Princeton. It was a closed and locked world. In studies we did in the investing domain, we found that race can influence professional investors’ financial judgments. Many people in the industry would like to create a culture that is more open and inclusive, but there is a powerful default assumption at work that acts as a barrier. In a lot of these firms, the default is still, “I know in my gut what a successful idea is and who is likely to build a company that can grow. I can see it and feel it, and either you match or you don’t match.”

It seems like a point of tension where the institutional level says it wants change, but at the interaction level, this is still a relationship-driven industry. So what do you do about that?

Hamedani: It depends where in the culture map you want to start. Let’s say you diversify the students coming in and getting MBAs. Then you have to look at how are they’re being mentored and supported through their schooling experience, through the internships and job opportunities that they have. Are you simply assuming that they should assimilate to the default? Are you training a new, exciting, and diverse group of people to act like those that have been there all along? Or are you incorporating their ideas and diverse ways of being that might look or sound different and affording them the same respect and status? Are you teaching them how to do a pitch a certain way because there’s only one right way to do a pitch? Or might they have other styles of communication or ways of selling an idea?

At the GSB, Jennifer has a class, Racial Bias and Structural Inequality, where she brings in all these amazing CEOs who are women and people of color. Most of the students, they’ve never seen it before. And that’s what happens to people in these investment firms: They haven’t seen it before. Even that intervention of seeing, week after week, these leaders coming in and the students get to ask them questions and have a conversation with them — that’s an interaction.

Eberhardt: I had Sarah Friar, MBA ’00, the CEO of Nextdoor, come in. I had the president of Black Entertainment Television, Scott Mills, come in; I had the police chief of San Francisco, William Scott, come in — they are both African American.

And the hope is that these students who will go on to work in the business world will have a broader definition of what is a “culture fit”?

Hamedani: Exactly right. And more specifically, a “leader fit.” And for women and students of color, that they can also see themselves as leaders. But it takes things happening at all levels in the culture map to make that happen. You’re seeding this change and then the levels are reinforcing each other to help it grow.

What would you recommend as a starting place for readers who are thinking that they want to spark intentional cultural change wherever they are?

Markus: It would begin with mapping the culture: What matters to us, what do we value? And then, to the extent that there’s some consensus about our culture, reflecting on whether our ways of doing things reflect this. In so many organizations we’re working with now, there’s really a gap between what leaders feel their values are, what they care about, and what the employees are experiencing. What we see is that it’s important to give the employees chances to get together to talk about this and have some company time, some paid time, to discuss these issues —

Hamedani: — to vision the future. Because there’s that virtue signaling, “OK, we care about that, but really we’re so busy and we have all these things to do. We have to hit our targets for the quarter or for the year.” Of course, those things are important, but are people — employees and leaders alike — participating in visioning that future and laying out the goals and objectives together? Can you make some small or even larger changes such that people feel empowered that they’re part of building that culture together?

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

For media inquiries, visit the Newsroom.

Explore More

Conflict Among Hospital Staff Could Compromise Care

Hardwired for Hierarchy: Our Relationship With Power