January 15, 2021

| by Alexander GelfandMatt Rickard, Republican senator from Iowa, is crowing about the climate bill he just helped turn into law.

Editor’s Note

In this ongoing series, we bring you inside the classroom to experience a memorable Stanford GSB course.

Against all odds, Rickard managed to convince his fellow Republicans to support a general carbon tax of $25 per ton while simultaneously persuading Democrats to accept a far lower tax on agricultural emissions. He even secured an unlikely amendment guaranteeing that some of that revenue would go directly back to farmers and ranchers.

“I was ecstatic,” says Rickard, noting that he got the best deal possible for his constituent farmers — who, it turns out, are entirely fictitious, as is his title.

The lawmaking took place in the elaborate legislative simulation at the heart of a Stanford GSB course titled I’m Just a Bill, taught by lecturer Keith Hennessey, a former senior White House economic advisor.

“This was probably the most complex multiparty negotiation I’ve ever done,” says Rickard, who succeeded in part by assembling an America Works caucus dedicated to protecting American industry. Still, the bill was almost undone by a presidential veto that Rickard and his fellow legislators managed to override at the 11th hour by only the thinnest of margins.

By the time the simulation was over, Rickard and other students had learned a great deal about real-world policy and legislative practice, both of which have an outsize impact on business and industry. But they may have learned even more about negotiation, coalition-building, and the importance of trust.

“This is in part a skill-building class,” Hennessey says. “And those soft skills should apply to any business environment.”

Legislation Simulation

Hennessey spent 14 years advising elected officials such as President George W. Bush and Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott on economic policy. Drawing on that experience, he developed a role-playing exercise that gives students a surprisingly realistic sense of what it takes to draft a bill, pass it through Congress, and have it signed into law.

And just like in the real world, it isn’t easy.

This year, because of the restrictions imposed by the coronavirus pandemic, 48 second-year MBA students initially spent four class sessions meeting under a pair of large tents in front of Bass Library and the CEMEX Auditorium.

Under Hennessey’s guidance, students learned the basics of the legislative process known as committee markup. Working in small groups, they mimicked what it is like for committee members in the House and Senate to consider legislation in four major policy areas (pandemic response, climate change, immigration, and economics), propose amendments, and vote on the results.

To streamline the process, Hennessey provided the students with worksheets describing different options for each policy area: a $10 versus a $20 carbon tax for the climate bill, for example, or a 10% decrease versus a 20% increase in the aggregate number of green cards for the immigration bill. Make selections from the policy menu and voilà: You have yourself a bill.

During the second week, students were encouraged to run for president, resulting in the election of Kanishka Narayan, a Democrat who made it clear that he would use his veto power to kill any legislation he did not like.

Narayan chose a chief of staff and a senior advisor for each policy area. Hennessey, meanwhile, assigned roles to the remaining students based on his observations of the initial practice sessions and a detailed survey of how the students felt about the various policy areas. Twenty students were assigned to a Republican-led House, 20 to a Democrat-led Senate, and two were cast as reporters representing the Washington press corps.

The simulation then began in earnest: Students were given basic guidance on the parts they were expected to play (Rickard’s character, for example, was modeled after Charles Grassley, the seven-term Republican senator from Iowa), then let loose to see how much of the people’s business they could get done before the semester came to a close.

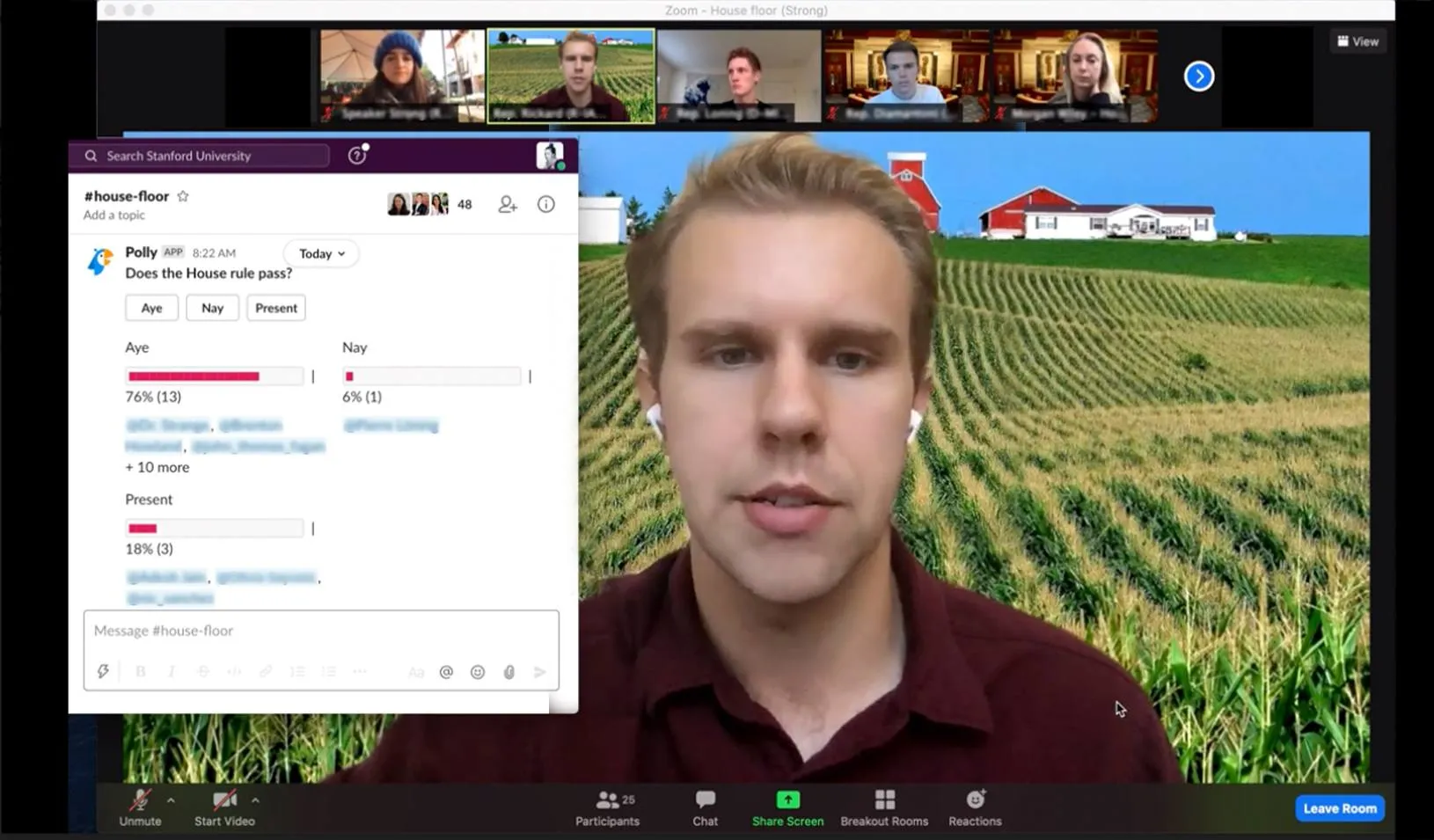

Once the simulation was underway, pandemic protocols meant that the class had to move completely online, with students interacting strictly through Zoom, Slack, texts, and phone calls. They posted bills, amendments, press releases, and statements to a virtual town square (#town-square); delivered impassioned Zoom speeches on the floor of the House and Senate; strategically leaked information to the press; and attempted to do deals at all hours of the day and night.

Hennessey concedes that the purely virtual environment made it impossible for the mock legislators to read one another’s body language, let alone glance around a room and instantly see who was engaged in private negotiations. But it did have certain advantages. Rickard, for example, appreciated being able to chat privately with other members via Slack while following a debate on the House floor.

Fully Immersive

While Hennessey sometimes refers to the simulation as a game, it quickly became all-consuming for the students.

“I was having dreams about it,” says Victoria Wills, whose own role as Senate Majority Leader (D-WA) was modeled after Lyndon B. Johnson.

In some ways, Wills had it easy compared to Rickard, who had to set aside his personal progressive politics and embody a staunch conservative. (The key, he says, was focusing on the impact that a particular policy like a carbon tax would have on his imaginary constituents.)

But that didn’t mean that Wills had it easy. Especially when she had to deal with people who did not share her priorities. “It was very hard not to take it personally,” says Wills, who as Senate majority leader was dead set on achieving a pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants.

One conversation she had with senior White House immigration policy advisor Emily Kazam even grew heated. Kazam played the part of a centrist Republican serving in a Democratic administration, a role that required her to act as a mediator between representatives of both parties. “I tried to be their thought partner, understanding and translating arguments for both sides,” she says.

But while her position as a Republican appointee serving a Democratic president helped Kazam establish rapport with GOP members of the House and Senate, it provoked suspicion among some Democrats — including Wills.

“I was pushing her really hard to compromise, and she was hell-bent on the pathway to citizenship,” Kazam says. “She accused me of advancing the GOP agenda and of not being on her side.”

Wills momentarily slips into character when she recalls the exchange: “I said, ‘The House bill is garbage. It’s not nearly compassionate enough, and I will fight to the death for a pathway for all undocumented immigrants.’”

The two quickly resolved their differences and Wills ultimately got the progressive bill she wanted, but only after invoking cloture to end a filibuster by Senate Republicans — “cloture” being a word that few people in the simulation could have defined before taking the class.

Game Changer

Wills says she gained an appreciation for the power of revealing one’s motives — and of getting others to reveal theirs.

“So often, people are fighting for several different things at once, and it’s hard to see what their bottom line is,” she says. Understanding what those around you need, however, can help everyone achieve their primary goals.

Kazam came to see a similarity between presidential advisors who must rely on indirect influence to shepherd bills through the legislative process and product managers who get results by negotiating priorities and motivating others.

And Rickard feels he honed many of the soft skills he will need to successfully launch a tech startup after graduation, such as generating enthusiasm for his ideas, negotiating with stakeholders, and building coalitions.

Then again, he gained such an appreciation for the legislative process that a future career in politics is now a possibility as well.

“It was eye-opening to see the depth and complexity of many issues I took for granted,” Rickard says. “I came out with a lot of respect for the work our legislators are doing. And I saw that there is still a lot of work to be done.”

For media inquiries, visit the Newsroom.