March 28, 2018

| by Louise LeeCASI Visiting Speakers

The Corporations and Society Initiative (CASI) hosts a variety of events for members of Stanford GSB, Stanford University, and the broader community to discuss the complex and interacting forces that impact corporations and society.

What’s a move that the U.S. could make that’s both business-friendly and worker-friendly?

Emulate Denmark, says Gerald F. (Jerry) Davis, author of the 2016 book The Vanishing American Corporation: Navigating the Hazards of a New Economy and a recent visiting scholar in the Corporations and Society Program at Stanford Graduate School of Business.

Denmark provides an array of social welfare benefits so companies don’t have to, providing workers and their families a guaranteed safety net, says Davis, who’s also a professor of business administration at the Ross School of Business at the University of Michigan.

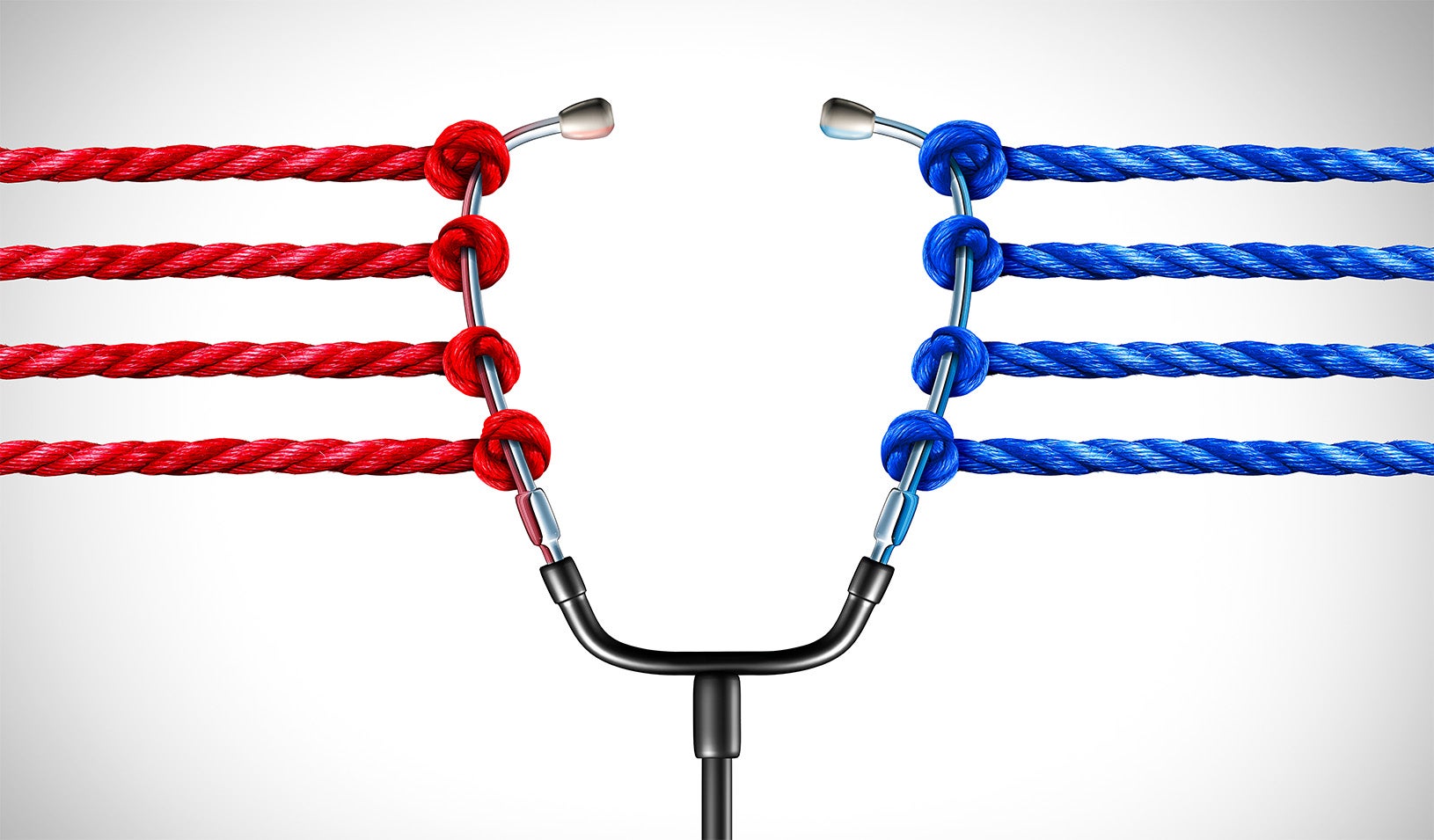

Both entrepreneurs and established companies in the U.S. would benefit from a Danish-style system, Davis says. It’s expensive to be an employer because of the health care, retirement, and other benefits that employees expect companies to provide. Those costs are high enough to discourage companies from hiring and entrepreneurs from launching a startup, says Davis.

“Because we’ve freighted the employment relationship with so many obligations, it’s hard to be an entrepreneur who creates jobs,” he says.

Of course, one alternative is to start a company but avoid hiring employees and instead farm out work to independent contractors or so-called gig workers. But that model, which plenty of young companies are already using, comes at cost to the workers, who don’t receive benefits and frequently can’t afford to buy health insurance on their own or save for retirement. That situation “creates huge uncertainty in your ability to get basic social welfare and provisions,” says Davis.

How did we get here? After World War I, individuals flocked to cities to work in large corporate-owned factories. Manufacturing workers earned relatively generous wages and often benefited from opportunities for upward mobility. “Whole families were taken care of” by Detroit automakers, says Davis. Under wage freezes during World War II, companies competed for workers by offering ever-richer perks, all of which people grew to expect from employers. This system was codified after the war in the so-called “Treaty of Detroit” that provided retirement benefits and health insurance for workers and their families.

The costs of being an employer became painfully evident in the 1980s, when retirees began cashing in on insurance policies and pension agreements negotiated decades earlier. To reduce costs and appease shareholders, companies began outsourcing, sending back-office and other administrative tasks to lower-cost contractors.

In the 1990s, companies began outsourcing not only peripheral tasks but also pieces of their core business, a trend Davis dubs “Nikefication,” after the shoe marketer known for delegating shoe manufacturing to independently owned factories in Asia. Rapid advances in information technology let companies easily transmit information to offshore facilities. Companies quickly saw they could function with fewer hard assets, such as factories, and with fewer workers expecting benefits.

In recent years, smartphones have made it easy and inexpensive to find workers to perform a specific task, paving the way for “Uberization,” the use of independent freelancers for all kinds of work. “The cheaper it becomes to locate and evaluate labor by the task, the more likely that we use task-based labor,” says Davis. “This is a model that could completely transform the employment relationship in America forever.”

Consequently, traditional long-term positions with regular wages and benefits are becoming increasingly scarce. “Workers might prefer such jobs, but there are so many pressures that make long-term employment tough” for the employer, Davis adds.

The U.S. is ill suited to the gig economy because benefits are so closely tied to the employer-employee relationship. “If we wanted to have a more vibrant business sector and more startups, then we should have a Danish-style social welfare system,” he says. Denmark isn’t an intrusive nanny state that strangles Silicon Valley-style entrepreneurs, Davis adds, citing the many thousands of startups that launch each year in a country of fewer than six million.

Because Danish entrepreneurs can start a business and hire without providing benefits, “a strong [government-sponsored] social safety net is a business-friendly proposition,” he says.

And of course, a Danish-style system in the U.S. would provide everyone with health insurance. That way, Davis says, the growing ranks of gig workers won’t have to worry about missing an insurance premium, getting sick, becoming homeless, and “having to live in their car.”

For media inquiries, visit the Newsroom.