Many Americans Don’t See Their Political Rivals as People. But That Can Be Fixed.

Researchers are looking for ways to convince partisans that conflict doesn’t have to devolve into dehumanization.

October 17, 2022

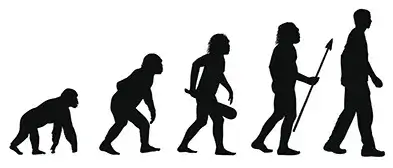

Seeing your opponent as less than human can erode democratic norms and even fuel violence. | Cory Hall

As politics in the U.S. have grown increasingly polarized, many people have begun to stake their sense of individual worth and identity on their party affiliation. To turn a slogan from the 1970s on its head, the political is now deeply personal.

The flip side is that many Americans no longer see their opponents as people who just happen to have different opinions. On social media and partisan “news” channels, it’s not uncommon to hear members of one side portray their rivals on the other as less than human.

To anyone who knows their history, this is alarming. “In the last century, dehumanizing propaganda — likening the Jews to vermin, or the Tutsi to cockroaches — prepared the way for genocide,” notes Alex Landry, a doctoral student in organizational behavior at Stanford Graduate School of Business. Even short of violence, studies suggest, dehumanization leads people to condone violations of democratic norms, putting the stability of our society at risk.

In 2020, Landry quantified the extent of dehumanization in U.S. politics using a scale pegged to a famous image depicting the “ascent of man.” Republicans and Democrats were asked “how evolved” they thought the other side was, from 0 (ape) to 100 (fully human). Shockingly, both sides placed their opponents about 20 to 30 points below fully human, on average.

A study used this famous image to ask Republicans and Democrats “how evolved” they thought the other side was. | Landry et al. (2021)

Yet there was an interesting catch: When asked how they thought the other side viewed them, people said their rivals would put them 60 points below fully human. Their perceptions of the other side’s contempt were grossly exaggerated.

“That might be the only good news in political science in the past decade,” Landry jokes, somewhat bleakly. “As bad as it is that Americans dehumanize one another — and I’d be the last to minimize this — they don’t do it nearly as much as people fear.”

In fact, he guessed, the tendency to assume extreme antipathy on the part of rivals might be driving some of the actual, overt denigration — a sort of preemptive tit-for-tat. It’s not hard to see how that could escalate into a self-fulfilling cycle of fear and aggression.

Yet might it also create an opening to short-circuit the process? Perhaps, Landry thought, if people were given accurate information about the other side’s attitudes, they might see their opponents as more human.

We the People

That’s the idea behind Landry’s latest paper, written in conjunction with Robb Willer, a professor of organizational behavior (by courtesy) at Stanford GSB and director of the Stanford Polarization and Social Change Lab; Jonathan Schooler of the University of California, Santa Barbara; and Paul Seli of Duke University.

The group tested a simple intervention. “Basically, we just told people the result of the earlier study,” Landry laughs. Incredibly, it worked. In three separate experiments, when subjects were informed that rival partisans dehumanized them less than was believed, they significantly reduced their own dehumanization. The effect persisted in a follow-up a week later, suggesting the intervention had some lasting influence.

“It has to give you some hope,” Landry says. “I mean, this was a 45-second message — just text, with no effort to pluck at heartstrings or evoke empathy. Social platforms could scale this up at almost no cost, and you could easily combine it with other techniques to bolster the effect.”

He notes that a similar intervention using a three-minute video was the top performer in the Strengthening Democracy Challenge, a recent effort to crowdsource scalable ideas for reducing anti-democratic attitudes. From more than 250 submissions, 25 were selected and evaluated in a recent mega-study coauthored by Willer and led by Stanford sociology doctoral student Jan Voelkel.

“We have this cold, cognitive correction,” Landry says. “When you humanize it by showing real political rivals disavow dehumanization — like, ‘No, that’s ridiculous. We may disagree, but they’re still human beings’ — that really levels it up.”

Why Do Humans Dehumanize?

Humans instinctively sort themselves into groups, Landry says, and as decades of research shows, the mere existence of factions sparks a contest for status. “If I derive my identity and esteem from being in one group, I will denigrate out-groups because it’s always a relative comparison.”

Dehumanization, he says, is a crude but potent way of asserting one’s superiority. To cast the “other” as subhuman is to consign them to a lower rung on the ladder of moral worth, thus less deserving of protection. “We all carry this hierarchy around in our heads as a way of organizing our moral universe,” Landry says. “For most people, humans are at the top, then nonhuman animals, then objects. You kick a dog, that’s pretty bad; you kick a rock, that’s totally fine.”

When someone portrays us in dehumanizing terms, he says, it threatens our core sense of self, and we dehumanize them right back. When two sides are fairly equal in power, as in the U.S., this “reciprocal dehumanization” can trigger a race to the bottom. And when people see insults lobbed by rival extremists, they exaggerate the extent of those attitudes in the group as a whole. “It’s a classic case of negativity bias in conflict,” Landry says. “Humans just innately tend to attribute malicious motives to out-groups.”

Willer says this has been a consistent finding at the Stanford Polarization and Social Change Lab. “One thing our research underscores is that American partisans have really inaccurate views of rival partisans — about their demographics, their attitudes and intentions, and how they view their opponents,” Willer says. “And those misperceptions shape their own attitudes.”

Pulling the ideas of reciprocal dehumanization and negativity bias together showed how dehumanizing rhetoric can spin out of control. But it also revealed a weak point in the vicious cycle that interventions could target.

When Rhetoric Becomes Real

Dehumanization in itself is corrosive. But Willer and Landry’s research suggests it also leads people to condone anti-democratic actions they would normally consider wrong. Could the intervention reduce that support? The researchers asked test subjects how strongly they agreed with some provocative statements. One example: “[In-group] should do everything they can to hurt [out-group], even if it is at the short-term expense of the country.”

Those who got the corrective information on dehumanization agreed somewhat less with these statements. “Not a huge improvement, but it was significant and promising as a direction to explore,” Landry says. “Targeting dehumanization at least seems to have more downstream effect than other interventions people have studied.”

Curiously, while Republicans and Democrats in the study dehumanized each other fairly evenly, and both reduced their dehumanization when presented with the corrective information, only Democrats reduced their support for anti-democratic actions. Landry says that difference was not statistically significant in his sample, but it’s worth following up on in future research.

As history tells us, the stakes are high. “The distance from genuine dehumanization to persecution and violence is very small,” Landry says. But do American partisans truly think their rivals are subhuman, or are such statements just weapons in a war of words, intended to insult and intimidate?

“I don’t know how much genuine partisan dehumanization currently exists in America,” Landry says. “This is actually my main interest right now, to dig deeper into the psychology and understand what’s going on below the surface.”

“But look,” he adds, “even if it’s a rhetorical tactic, the fact that we’re constantly exposed to this now in the media, from our political leaders, is dangerous. We can’t let this be normalized.”

For media inquiries, visit the Newsroom.

Explore More

Billionaires Can’t Solve Our Problems, Says ‘Davos Man’ Author

Yes “We” Can: Swapping Pronouns Can Make Messages More Persuasive