November 15, 2014

| by Ian ChipmanIn the developed world, innovation is nearly synonymous with high-tech products streaming forth from multibillion-dollar companies. And yet, some of the most striking lessons in achieving scalable solutions to persistent challenges can come from the most under-resourced areas, and with little to no technological wonders.

Stanford professor Stefanos Zenios, an expert on the intersection of technology and health care, sheds light on one such instance in a recent paper he coauthored and published in the American Journal of Nursing.

He and his colleagues found that one hospital in Bangalore dramatically reversed its high rate of a common hospital-acquired infection by implementing a strategy that balanced simplicity with sustainability. Any hospital around the world could benefit from understanding the foundation of its success.

Teaming Up

In 2009, Zenios and a team of other faculty across Stanford University’s schools of business, engineering, design, and medicine were awarded a grant from the National Institutes of Health to develop a multidisciplinary Consortium for Innovation, Design, Evaluation and Action in global health. The business school’s primary role in the consortium was to investigate health care advances in developing economies in order to help entrepreneurs tackle global health challenges. More specifically, they wanted to better understand how global health innovators could more effectively scale up their good ideas in emerging economies where conditions are complicated and resources are scarce.

The team gathered dozens of case stories from innovators and organizations spanning five continents. Their journey also brought them into contact with Devi Prasad Shetty, the founder, chairman, and managing director of Narayana Hrudayalaya Cardiac Hospital in Bangalore, India (now known as the Narayana Institute of Cardiac Sciences). One of the world’s largest cardiac hospitals, NHCH is known for its ability to balance high volume, quality care, and low cost. Shetty suggested that the researchers take a look at the hospital’s initiative to address a rise in hospital-acquired pressure ulcers, also known as bedsores, which are common complications of surgical procedures.

Their simple, effective solution impressed the researchers on a number of levels.

“They developed and deployed a process widely within the hospital system without using any technology,” Zenios says. “Sometimes we, in the developed economies, can learn from what organizations in developing economies do with limited resources.”

Tricia Seibold

The NHCH Success Story

In early 2009, Shetty was troubled by the rise of pressure ulcer incidence that accompanied a spike in the number of cardiac procedures performed at NHCH.

Hospital-acquired pressure ulcers are not only painful for patients and a burden on health care costs, they are also widely viewed as an indicator of nursing care quality. One study suggests that each year over 2.5 million people in the United States develop pressure ulcers, and the length of a hospital stay nearly doubled when a patient developed a pressure ulcer.

“Patients don’t come to the hospital with pressure ulcers,” Shetty told the researchers. “It is something we give them.”

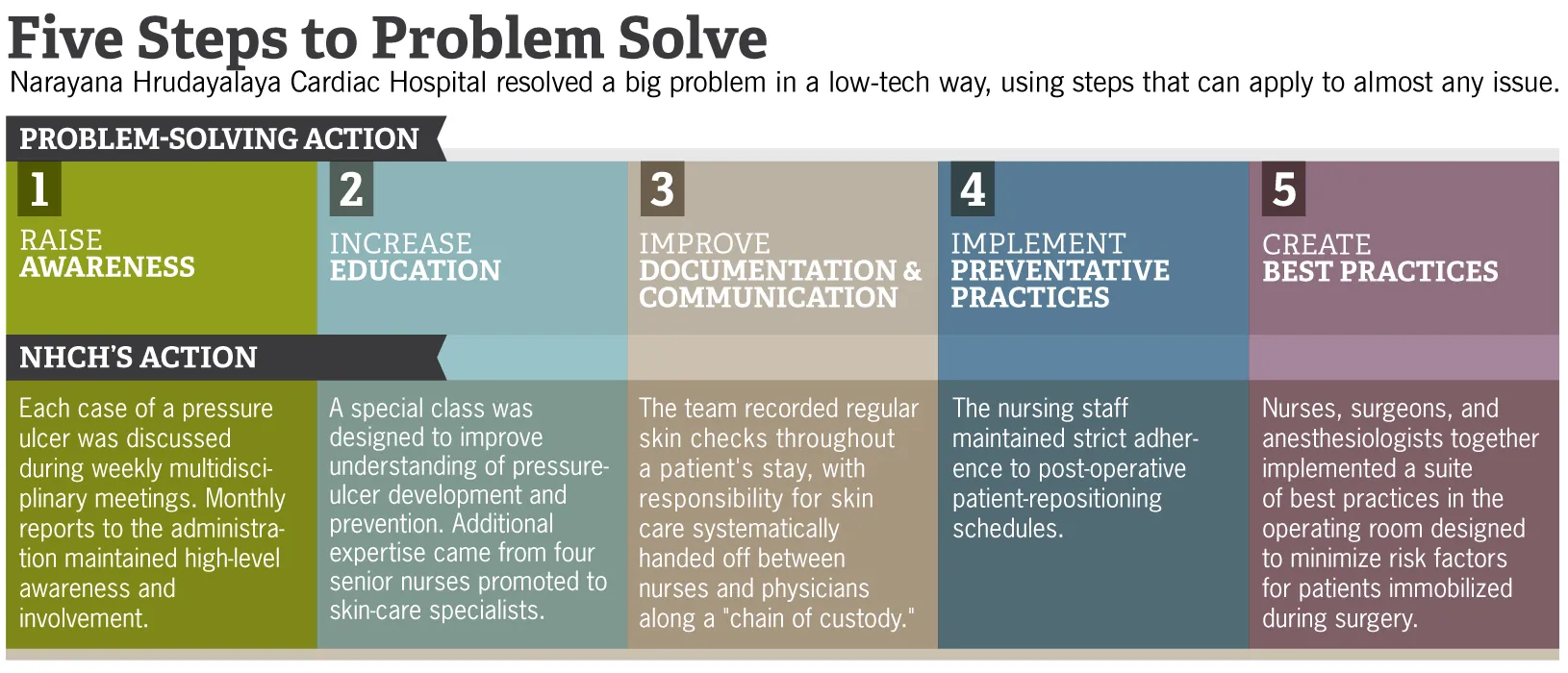

He initially tasked a small nursing team with devising and implementing a prevention strategy. While it is often considered the nurses’ responsibility when pressure ulcers develop, they are often powerless to influence the chain of events that lead to them. So the executive leadership made a point to educate and involve the physicians as well as the nurses — something that pressure ulcer prevention programs in the United States rarely do — and asked the nurses to suggest changes to operating-room procedures.

Before long, every one of the hospital’s nurses, surgeons, and anesthetists was involved. The staff overhauled the paper documentation process to track every instance of a pressure ulcer, and singled out the individuals responsible when one arose. Each case was also discussed in detail — constructively, not punitively — during weekly meetings attended by all department heads.

These protocols resulted in increased transparency and heightened personal accountability, which were key to this program’s success. In fact, the researchers found that investigating staff performance and providing constructive feedback was missing in most other systematic pressure ulcer prevention programs.

This alignment of bottom-up education and top-down leadership worked wonders. At the outset of the program, an average of 6% of patients experienced a pressure ulcer during the course of their recovery at NHCH. After six months, the team not only reduced the rate of pressure ulcers, they eliminated them entirely. Four years later in 2014, that rate remains zero.

All too often in large organizations, Zenios says, when a problem is everyone’s problem, then it’s no one’s problem. Here was a case where making the solution everyone’s responsibility led to a collective wellspring of pride and success.

“It was the personal responsibility that started making a difference,” one nurse told the researchers. “Now everybody’s aware, everybody’s cooperative and on their toes, and we have no skin ulcers.”

Takeaways

The program’s initial success and subsequent sustainability were rooted in its simplicity and emphasis on the human capital at one’s fingertips rather than high-tech solutions. Instead of investing in pressure-redistributing mattresses and other costly equipment, staff devoted time and careful attention to patients’ skin care. And rather than tracking it all through electronic medical records, which can be confusing and not accessible to all staff members, they developed systematic improvements to paper documentation and fostered a culture of communication.

“There is this belief within the U.S. health care system that technology is going to be a big component of the solution,” Zenios says. “I think what this case demonstrates is that well-targeted, low-technology approaches can make a huge difference. It provides a template of how you can focus on a particular problem, identify the root cause, create targeted interventions, and then come out ahead in the end. These targeted interventions do not necessarily need fancy, complicated technologies.”

Not only is the approach used by NHCH a lesson in stretching limited resources, but it’s also an example of a solution that is scalable precisely because of the effort and resources put into it, not in spite of them.

“You want to be looking for those cases where the problem you’re going to prevent, by devoting more attention earlier, is a problem that becomes much bigger if you don’t,” Zenios says. “This is one of those examples where you’re coming out ahead by relieving burden.”

Whether you’re running a hospital or any other organization that’s stressed for time and money, this is a valuable lesson.

It all comes back to one of the fundamental building blocks of medicine, and one that all too often gets overlooked. “Prevention,” says Zenios, “is much better than treatment.”

For media inquiries, visit the Newsroom.