May 14, 2019

A couple of years ago, Sylvia Klosin was working on her undergraduate degrees in economics and statistics at the University of Chicago when she began to think about getting a PhD.

She’d loved economics since high school and was confident in her abilities but usually found herself one of the few women — and sometimes the only woman — in the classroom. It wasn’t unusual for those around her to question whether as a woman she had sufficient “natural talent” to pursue a math-based career.

“I reached out to one faculty member for advice on pursuing graduate school,” she recalls. “He basically told me to stop worrying so much about graduate schools, because grad schools were looking for stars, and I wasn’t going to be a star. My career would be supporting the work of others. This was really frustrating, especially since this same faculty member was being very supportive of a male student who was getting lower marks than me in classes. It was definitely very painful.”

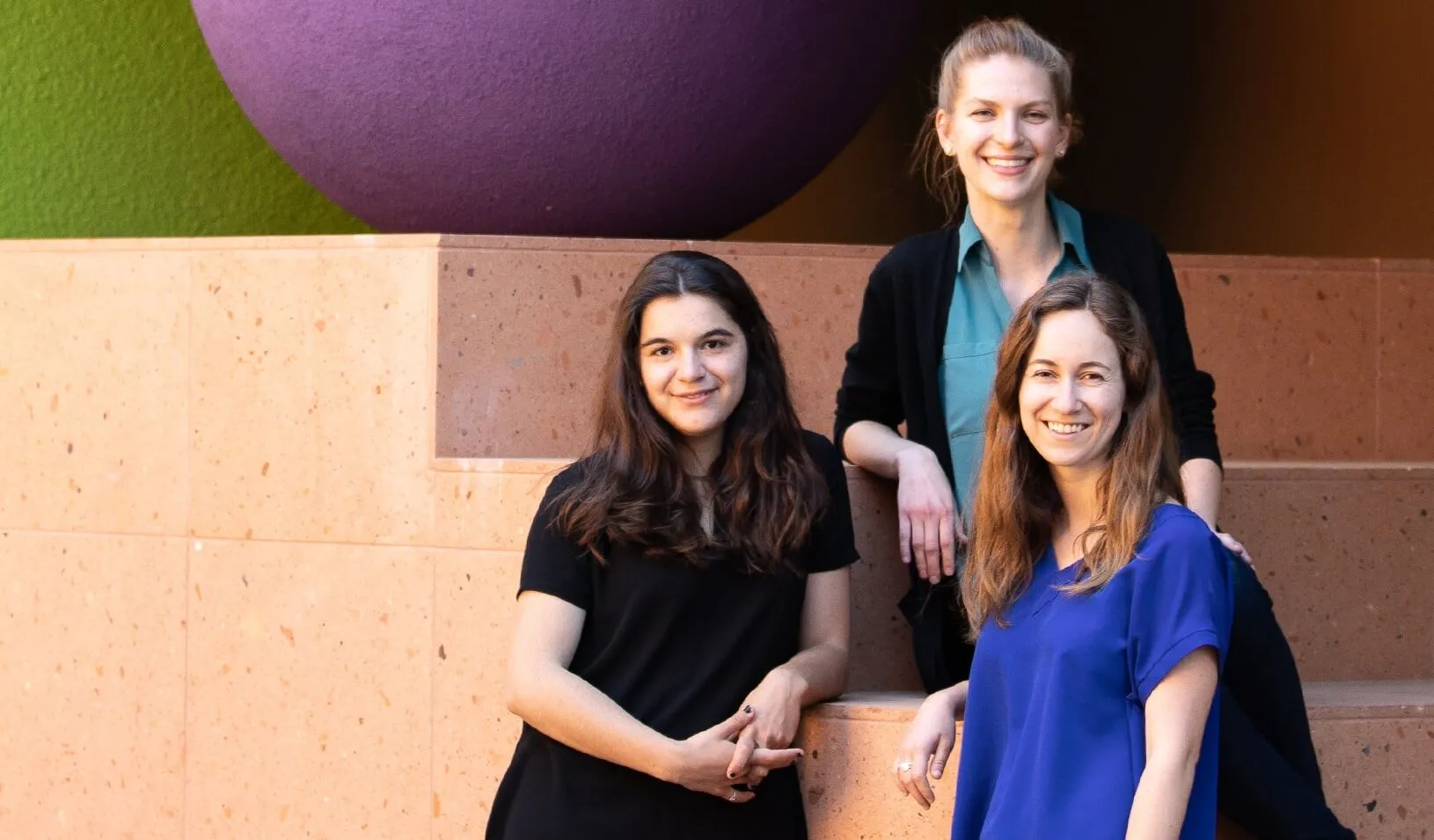

Today, Klosin is a passionate advocate for women in economics and one of three women due to graduate this spring from the Stanford GSB Research Fellows Program. For the past two years, she’s honed her research skills, taken PhD-level courses, and absorbed mentoring advice from top faculty at Stanford Graduate School of Business. She’ll begin her PhD program in economics at MIT in the fall, guaranteeing that her voice, her passion, and her potential will contribute to the field of economics.

Providing a Path

Experiences like the one Klosin faced as an undergraduate — and may continue to face in her career — are far from rare for women and minority students attempting to enter fields, such as economics, that have traditionally been dominated by white males. The Research Fellows Program works to counter that reality by providing vital support at one of the most critical junctures in a student’s academic life.

The proposal for the unique, two-year program at Stanford GSB was first drafted in 2012 by management lecturer Robert Urstein. It launched in winter 2014, thanks to the combined efforts of faculty members Susan Athey, the Economics of Technology Professor; Wesley R. Hartmann, the John G. McCoy–Banc One Corporation Professor of Marketing; and Lanier Benkard, the Gregor G. Peterson Professor of Economics, who served as the program’s first faculty director.

The goal was twofold: Strengthen the diversity pipeline leading into business fields by helping a varied and promising group of post-baccalaureate students prepare for graduate school, and provide support to the growing number of empirical researchers at the university. Program Fellows — many of them women and underrepresented minorities — train in complex data analysis by working as research assistants. They are also able to take one PhD-level course each quarter, to deepen their preparation and round out their transcripts, and receive consistent mentoring from a range of faculty members. Most of the students have an economics background, while others come from such fields as computer science, math, and political science. When the program began, there were three students in the first cohort. That number is expected to exceed nine this summer.

“The program is open to anyone looking to pursue a PhD in business or a related field and who needs additional experience to be successful in doing so,” said Dianne Le, executive director of PhD program administration at Stanford GSB. “For all of our Fellows, and especially for our women, the learning curve when joining a doctoral program will be in part academic and in part everything else. The ‘everything else’ includes ‘How do you make sure you’re heard when others speak over you? How do you speak up in a seminar when your thoughts may not be fully formed? How do you manage self-doubt and convince yourself you deserve to be here?’ There are all these different dynamics in being a woman in this space and how to be effective there.”

The coursework and research experience available from the program are valuable assets when applying to prestigious, risk-averse graduate programs, says Athey.

“If the person has already taken a first-year PhD class and succeeded in it at a top school like Stanford, you’ve just removed a huge element of risk for the programs they’re applying to,” she says. “They can also demonstrate having developed relationships with professors who can attest to their creativity and research potential.”

Research Fellow Helena Pedrotti was raised in Santa Cruz, California, a city that struggles with a large homeless population. She’ll graduate from the program this spring along with Klosin, and is interested in the economics of homelessness. She entered the program after studying math and economics at Reed College and will begin her PhD program in economics at New York University in the fall. She says she’s grateful to have been exposed to a range of different fields and research styles.

“Students coming out of this program have a huge edge over people who are just applying out of undergraduate school, or even from industry, honestly, because academia is a very special beast,” she says. “It has its own rules and norms and expectations, and I think we all have a much better grasp of them having been in this environment for the past two years.”

Diversifying the Pool

Stanford GSB’s program is distinct from other pre-doctoral offerings around the country both because of its location within a business school and because it has a specific goal of adding more women and minority students to the small and select pool of graduate school applicants around the country.

“The diversity component was something I’d always thought about, but this exceeded all my expectations,” Athey said. “If you can actually train more people to be in that pool, then you’re moving the needle. You’re making that pool more diverse. That’s what this Research Fellows Program has the opportunity to do.”

A lack of diversity in any field can result in serious and long-term consequences, said Sarah A. Soule, the Morgridge Professor of Organizational Behavior and senior associate dean for academic affairs at the business school.

“Diversity is linked, again and again, to innovation,” she says. “If we don’t strive for diversity, we risk failing to innovate, and this is a real problem, especially in academic endeavors, where innovative ideas are the currency.”

Because the program also focuses on mentoring, fellows receive the type of ongoing support and encouragement that often was lacking during their undergraduate years. Klosin, who’s interested in econometrics and the labor market, is no longer being discouraged from her dream.

“I’ve spent the last year and a half working with Susan Athey, one of the most powerful women in our field,” she says. “What’s really been awesome is that in addition to talking to her about research and the projects she’s working on, I’ve had amazing conversations with her about confidence. At one point, I was having a really low week and wondering if I had what it takes. She was more than happy to spend time talking to me about her experiences.”

Fellows also enjoy a peer relationship with other PhD students and an inclusive environment where their contributions are valued.

Building the Network

Research Fellow Sara Johns studied environmental science and economics at Northwestern University before joining the Research Fellows Program. She’ll graduate from the program this spring and begin the PhD program in economics at the University of California, Berkeley, this fall. She hopes to contribute to the work being done on climate change by investigating the role economic incentives play in solutions to environmental problems. Like Klosin and Pedrotti, she appreciates being able to connect with other women entering the field.

“Growing up, even from a young age, there’s always the feeling that fields such as math or economics are not necessarily places for women,” says Johns. “You look at your teachers and professors and you see there are fewer women there. You don’t see people who look like you, and it can change the way you think about the field. I think here we’ve developed confidence being around each other, feeding off each other, and becoming more identified in how we talk and think about things.”

Those connections have already begun to form a network, as current Fellows reach out to program alumni for advice on coursework and doctoral programs, and as alumni return for visits and give feedback on the program, says Le.

“One thing I wasn’t anticipating was the level of community in this program,” she says. “The idea that mentorship between the fellows is expanding beyond Stanford is incredible. They’ll belong to a network of people that spans the country.”

Klosin, Johns and Pedrotti — each of whom recently received the prestigious National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship — are now preparing for grad school and potential careers contributing to the body of knowledge in labor, climate change, and homelessness. Each says she intends to continue advocating for women in economics.

“I know it’s going to be really hard, but I love economics, so I’m going to keep on persisting,” Klosin says. “I used to be a part of a group called Oeconomica, where we mentored underclassmen women. Telling them what I wish someone had told me was a great way for me to feel better about the future of the field, that ‘Hey, we’re going to make it better one day.’”

— Beth Jensen

For media inquiries, visit the Newsroom.